Volunteer Nikita Salt introduces William De Morgan’s support of Women’s Suffrage for International Women’s Day.

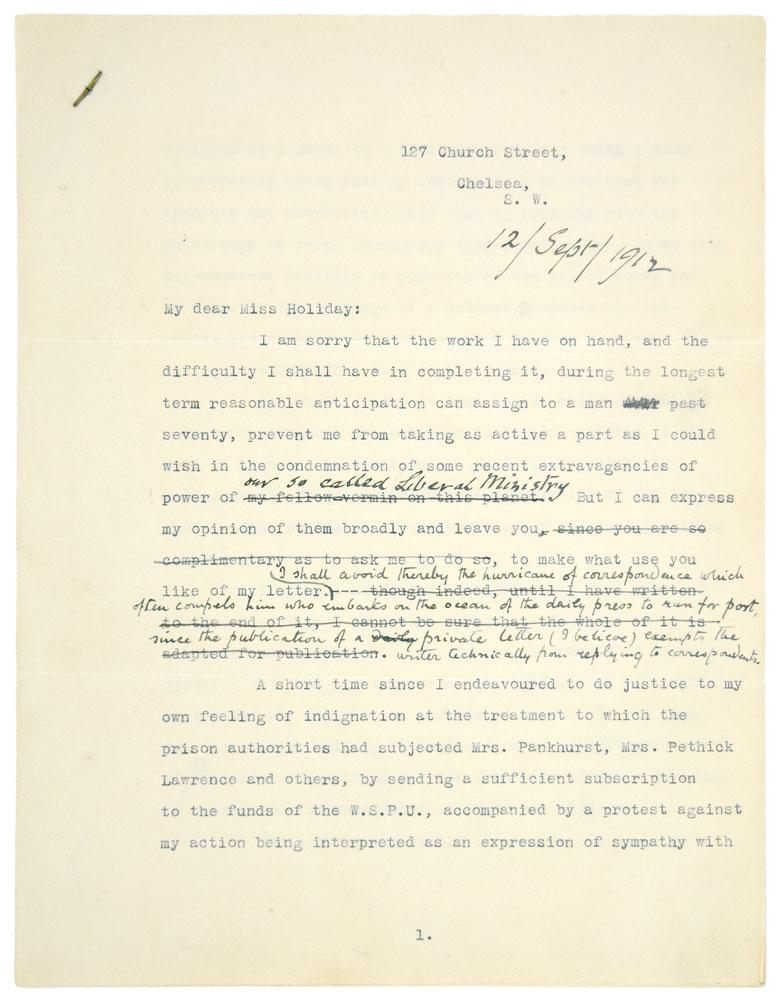

In 1912 William De Morgan sent a letter to Winifred Holiday (1866-1949) a famous violinist and Suffragette. She was also daughter of De Morgan’s good friend Henry Holiday, an illustrator well respected in the field of stained-glass and the man who in 1863 first introduced De Morgan to William Morris. The contents of this heavily redrafted and edited letter are a passionate argument in support of the women’s suffrage movement and a strong condemnation of the sitting liberal government, to be published and used by Winifred however she saw fit.

The year had seen yet another failure of the House of Commons to pass the Conciliation Bill intended to extend suffrage to women. Variations of the bill had already failed in 1910 and 1911 for various reasons, including Prime Minister Asquith’s call for a disruptive general election that prevented further parliamentary progress on the 1910 bill, despite it having passed through two parliamentary readings with solid majorities. With Asquith still at the helm of government in 1912 and yet another failed bill on women’s suffrage, a path of more militant action began to be carved out by Emmeline Pankhurst’s WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union). 1912 was a flashpoint in which anger ignited and more powerful acts of dissidence were resorted to, the WSPU smashed up windows along Bond Street and hurled stones down Downing Street in protest. In turn these actions were met with extreme and aggressive response from the government, including mass-imprisonment, which ultimately led to the renowned hunger strikes by the incarcerated suffragettes.

While De Morgan was keen to assure of his ‘condemnation of violence’ in any form in his letter, his primary concern was the hostile reaction from the institutions of the government and the prisons.

He railed against the ‘recent extravagancies of our so called Liberal Ministry’ (a handwritten statement of reduced anger found above his erased dictation of ‘my fellow vermin on this planet’), and expressed ‘indignation’ at the treatment of ‘Mrs. Pankhurst, Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence and others’ at the hands of ‘the prison authorities’, which he considered both ‘a shameful torture’ and ‘a new mediaeval horror’.

He continued his concern with the matter of the official justifications of force-feeding of the women prisoners. Their lines claimed forced feeding was resorted to in order to ‘preserve these victims of “hysteria” from the possible consequences of a self-imposed martyrdom’. But De Morgan decried this as ‘simply so much hypocrisy’ with truer motivations lying in the fact that ‘the official soul was trembling for its own safety’, for ‘suppose that one of these infatuated women’, whom De Morgan credits as ‘singularly determined and clear-headed’ rather than hysterical, ‘had succeeded in dying!’

The well-argued letter is not an isolated incident of De Morgan’s support of the suffrage cause; he was a longstanding supporter of the WSPU and vice-president of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. But this reflection on his written words in 1912 is intended to reveal just one powerful fragment of De Morgan’s personal expression of support. He was a man that was clearly infuriated with the treatment of the suffrage movement, and one who turned that indignation into flourishes of the pen. He chose to help in the pursuit of women’s equality and dedicated time and effort to that end. We may all learn something from the solidarity that he enshrines, that it is not just the responsibility of those affected to fight for their own rights, but a duty for those who have a voice more likely to be heard to speak up.

Inequality has certainly not ended, and the hard earned gains of suffrage were not inevitable nor are they eternal constants or certainties that cannot be overturned. It could be argued that the current government’s attempts to curtail supposed voter fraud through the introduction of Voter ID may cause modern disenfranchisement. Voter ID will deprive those unable to produce photo ID of the vote, affecting some 2 million UK voters (of which a very small minority, by last month just 0.5% of them, have applied for photo ID that will allow them to a vote).

To end this article I leave you with De Morgan’s concluding, though not entirely optimistic, words. Words that brim with righteous anger, and may hopefully inspire us all to express our own solidarity and produce our indignant outbursts at the injustices of the world, with whichever choice words our passions lead us to:

‘I hear surprise expressed that the disclosures of the released prisoners have not produced a storm of indignation throughout the country. I feel no surprise myself. My fellow-countrymen have become so convinced that a Prime Minister [H.H. Asquith] who can command a bare majority in the Commons is, if not the Vicar of God on earth, at least one of His curates, that they are not likely to become excited as a body about any outrage on a plaguy woman with political views, short of rape or murder. It is true that a small minority are good and courageous – all honour to them for it! – but a huge inert mass of stupidity and moral laziness has to be moved to produce any outburst, that would deserve historical record, of anything that could be called indignation. Its constituent members are too busy living up to their jam-pot collars and stove-pipe hats to join in ‘shrieks’. This present epistle is a ‘shriek’, but not one that will rouse them from their torpor.’

ft: The sitters for Holiday’s watercolour, The Duet (exhibited in 1878), were Xie Kitchin and Winifred Holiday.