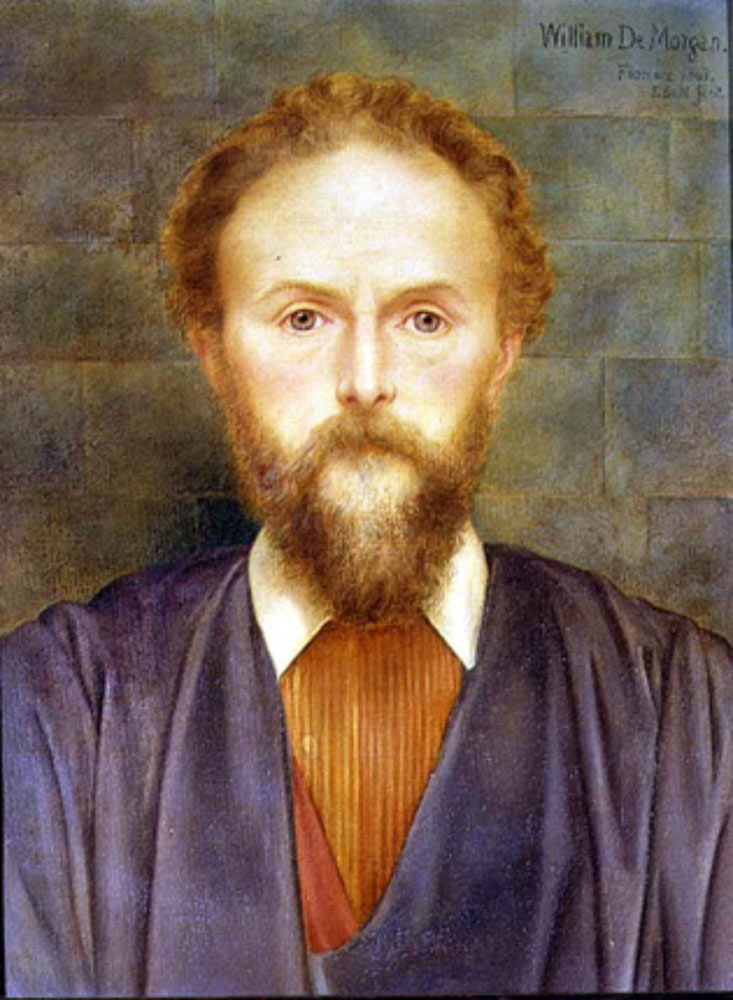

William De Morgan (1839 – 1917)

Family and Early Years

William De Morgan (1839 – 1917) was far more than William Morris’s potter friend, as he is often remembered. He was the most inventive and innovative designer of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

He began his formal training as a fine artist, before being led by his scientific and mathematical investigations to the decorative arts, creating stained glass, designing his own kilns, undertaking investigations in chemistry to create innovative lustre glazes and, finally, enjoying a second career as an author of popular fiction.

William was the eldest child of Sophia Frend and Augustus De Morgan, two liberally-minded and progressive parents. Sophia was a social reform campaigner, who wrote widely on the social issues she passionately supported, such as prison reforms, anti-vivisection and the abolition of slavery.

She assisted in the founding of Bedford College, London, the first teaching college for women, where she persuaded her husband to lecture. Augustus was the first Professor of Mathematics at University College London, a position he achieved aged just 21.

Augustus was a remarkable mathematician, a principal authority on formal logic, reason, and understanding and interpreting negative and decimal numbers. He published widely on the subject, for academic purposes, and also wrote extensively for the Penny Cyclopaedia, a cheap publication which allowed him to share his work with ordinary people, which was of great importance to him. Going against the norm of a church wedding, William’s parents married at St Pancras Registry Office, cementing their relationship in a secular ceremony to reflect their rejection of institutional religion.

Book I of Euclid’s Elements is the most entrancing novel in literature

William De Morgan, in William De Morgan and his Wife (1922) by Wilhelmina Stirling

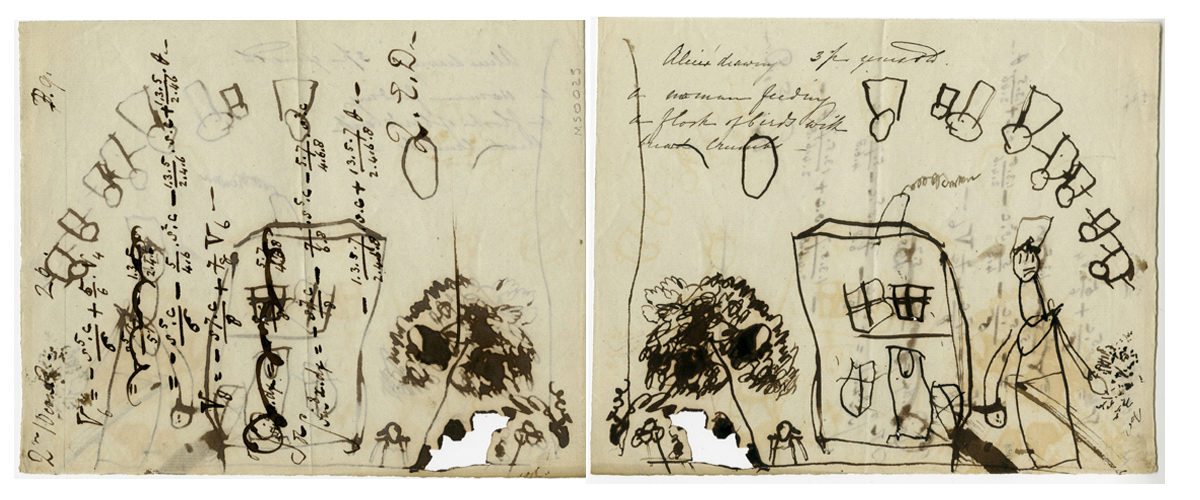

Growing up in this academic and liberal household impacted upon William. From a young age, William and his siblings were encouraged to draw, often using the classwork of his father’s students to doodle on, which exposed him to the visual element of mathematics.

William later attended his father’s classes at the University College Schools, where he would have studied Euclid’s linear geometry, which he held in such high regard. His interest in mathematics is evident in his ceramic designs, as he followed geometric form and convention to create symmetrically beautiful pieces.

Formal Art Training

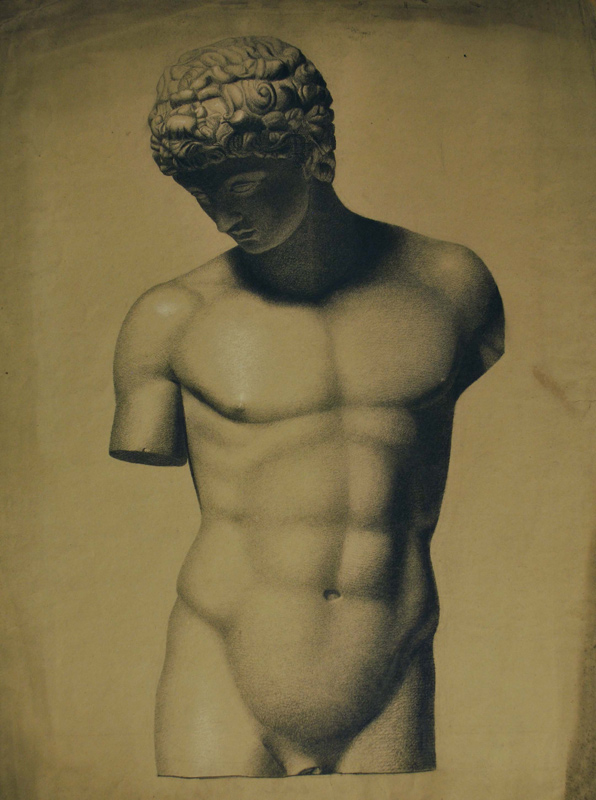

William never expressed more than an interest in mathematics and instead set out to become an artist, despite his father’s protests that this was an unstable career. He enrolled as a pupil with Stephen Francis Cary at his art academy in Bloomsbury, which had been established by his predecessor, Henry Sass, specifically to teach drawing from the antique to aspiring Royal Academicians. William’s sensitive, sculptured studies of classical antiquities from this period are exquisite. These drawings have been previously misattributed to William’s artist wife Evelyn, due to their perfection, but the inscription ‘Drawn at Cary’s’ in William’s handwriting has recently revealed the true artist. The merit of these brilliant drawings earned William a place at the Royal Academy of Arts in London where he studied fine art under Charles Eastlake from 1859 – 1863.

In his own words, William ‘never became a Real Artist’

William De Morgan, in William De Morgan and his Wife (1922) by Wilhelmina Stirling

In 1863, William De Morgan met William Morris at his studio at Red Lion Square, having been introduced to him by fellow artist Henry Holiday. Whether it was Morris’s abundant enthusiasm for the decorative arts, or William’s disillusionment with his own attempts at easel painting at this time is undocumented, but either way, it was after just four of his mandatory eight years of study and upon this pivotal meeting with Morris, that William dropped out of the Royal Academy Schools to pursue a career as a designer, rather than becoming ‘a real artist’.

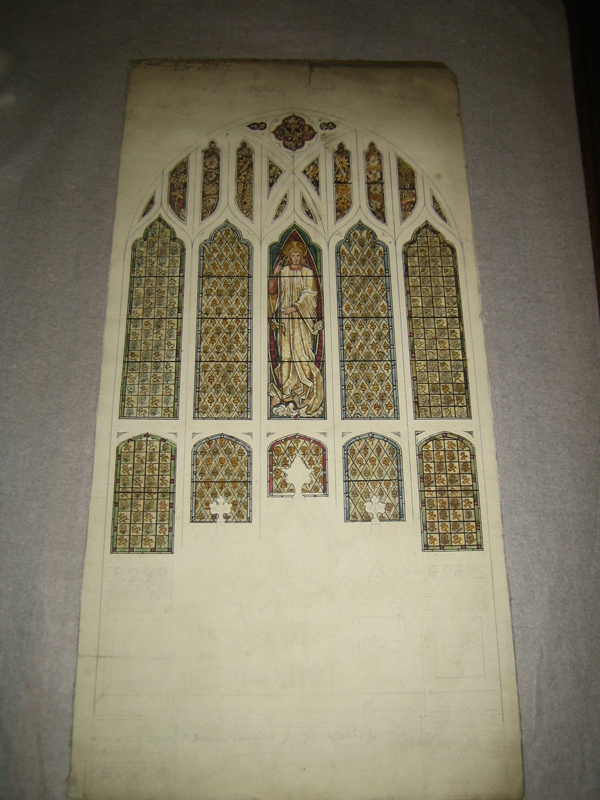

Setting out on his design journey: Stained Glass and Lustre

Probably at William Morris’s suggestion, in the 1860s William began designing stained glass and furniture. He used his classical training to create beautiful scenes from the Bible and from mythology, in harmony with floral patterns. His grasp of architectural schemes, three-dimensional drawing and manipulating ideas into drawings and designs in order to communicate them is demonstrated in the Foundation’s rare collection of William’s studies for stained glass.

It was the scientific investigations into method and making that really drove William’s career through the decorative arts. True stained glass can only be yellow, as this is the colour that is produced when the glass is painted with silver nitrate and fired in a glass kiln. Other colours of stained glass are created as ‘pot metal’, a layer of colour added to the molten glass during production. William was by nature an inventor. He worked practically on staining glass, noticing that if the kiln became starved of oxygen during firing, a metallic deposit of silver oxide would be left on the surface of the glass, giving it an opaque, iridescent finish.

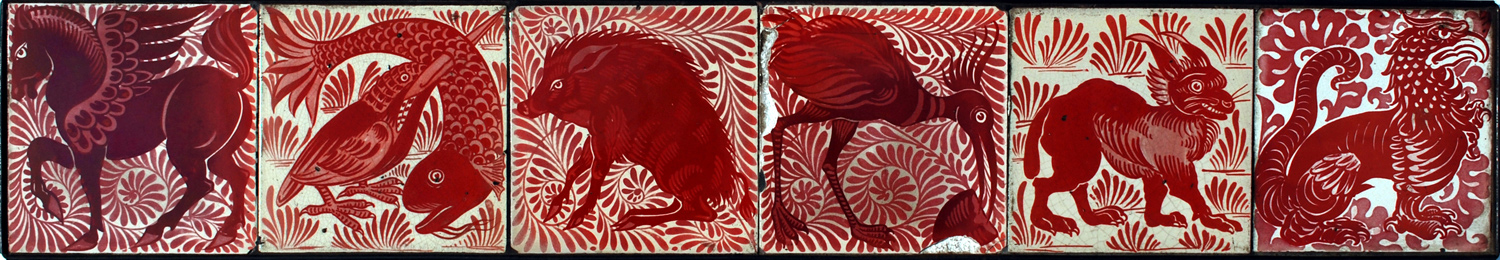

William noticed that this method must be similar to the ancient technique of lustreware, beautiful ceramics produced from the 9th Century in Egypt before spreading through Syria to the wider Middle East and Europe, where it was produced up to the Renaissance. William was deeply interested in this lost glazing technique, which requires a silver or copper oxide to be applied to the ceramic, and fired in a kiln starved of oxygen to force a chemical reaction to remove the oxygen from the glaze and leave a thin film of the metal on the surface of the ceramic. His interest in reinventing and perfecting this technique, plus the fact that there was no established ceramicist to supply the popular Arts and Crafts homes with tiles, led William to establish his firm in Chelsea in 1872, after he blew up his rented accommodation in Fitzroy Square whilst experimenting with a makeshift kiln in the hearth.

William’s early attempts to produce lustre are crude and naively executed, with motifs such as this dragon and owl, (above) which lack robust form or modelling. De Morgan developed the lustre technique throughout his career and soon became recognised at the world’s leading authority on the subject, speaking to the Egyptian Government on his process in 1892. His ‘Moonlight Lustre’ produced in the 1890s combined both copper and silver oxide glazes to give the effect of delicate moonlight having coloured his ceramics.

The Chelsea Period 1872 – 1882

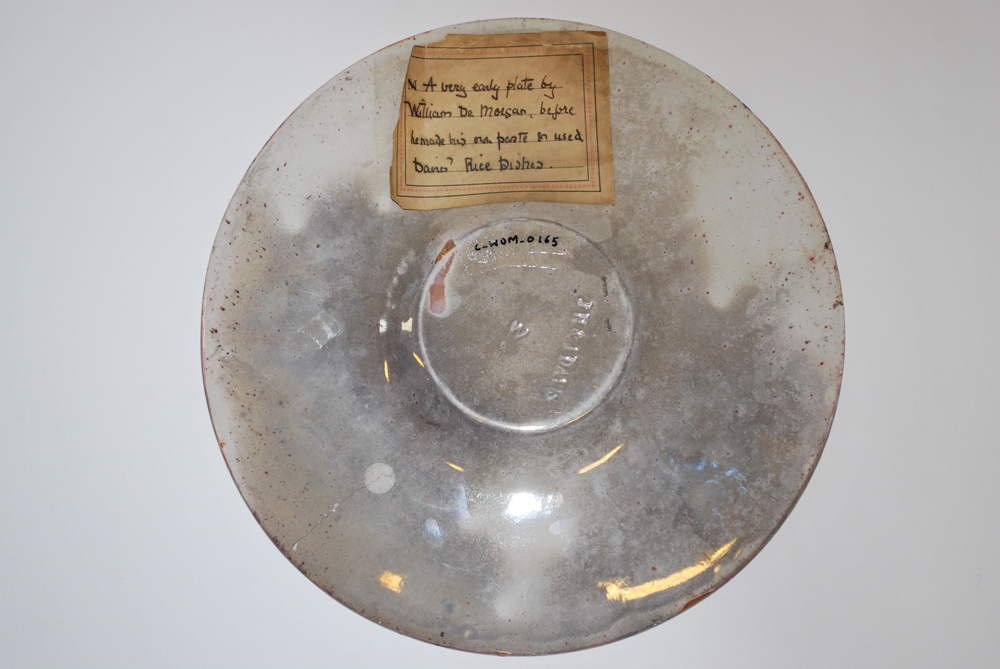

William’s early ceramic productions were dictated by the space available to him in which to produce them. His first premises was a terraced house on Cheyne Row, Chelsea, where he lived with his mother and sister. Space was at such a premium that De Morgan was unable to throw his own pots, something which he never learnt to do. Instead, he bought in blank plates and tiles from suppliers such as Wedgwood, the Morgan Crucible Company in Battersea, Poole Pottery and J H Davies.

William’s early works exploit the geometric properties of these square tiles and circular plates to ensure that his designs were not limited in scope by the limited surfaces available for decoration. For example, his Rose and Trellis design may seem naive, but the medieval ‘diapered’ or quartered element allows for this single tile design to be installed both horizontally and vertically, or to be rotated to create a variety of patterns if installed over a wall. This design, and many from the Chelsea Period, rely on simplistic medieval design techniques, not just for the ease of adapting them to basic shapes, but due to the Arts and Crafts and Gothic Revival Movements, led by Victorian revolutionaries William Morris, John Ruskin and A. W. N. Pugin, advocating medieval design above all others. In order that William De Morgan produced commercially successful designs which would compliment a popular Morris & Co. interior, his designs were led by his friend.

Merton Abbey Period 1882 – 1888

The Arts and Crafts movement of which William De Morgan was a key proponent, advocated that decorative arts should be handmade with traditional methods and that a singular piece should be made by an individual artisan. In order to pursue these dreams, William De Morgan had to move his expanding business from Chelsea to a site where he could direct staff to throw pots to his specification, thus finally fulfilling his ambition for a truly holistic approach to creating.

William Morris had already established a factory in Merton, near Wimbledon, and so in 1882, William De Morgan moved his business to be closer to his friend. At the peak of this period, De Morgan & Co. led around 40 employees to man the kilns, paint ceramics and throw pots, all overseen by William De Morgan.

William’s designs during this period became elaborate, ambitious and show his ability to design a three-dimensional surface as well as the complimentary two-dimensional pattern to cover it. Fish and Net Vase is a masterpiece from the Merton Abbey Period. The complex pattern of tessellating scale shapes twists around the spherical bulb of the vase, and expands as it bulges outwards over the body from the tight neck. It completely complements the shape of the vessel it has been designed to cover.

William was known for his good humour and a closer inspection of this vase reveals a hidden shoal of fish which have been captured in the net pattern. Incredibly difficult to produce, this double surface design was executed in the wax resist technique. The net pattern would have been drawn on the vase in wax after the first firing, with the fish then painted over this in the lustre glaze. The heat of the kiln would melt the wax revealing both patterns when the vase was removed from the kiln.

Italian Escapades and the Cantagalli Collaboration, from 1890

William married the artist Evelyn De Morgan in 1887 and travelled regularly to Florence with her, to visit her uncle John Roddam Spencer Stanhope. After 1890, the De Morgans had their own apartment in Florence and would spend the winters there, avoiding the cold London weather on account of William’s health.

Whilst in Florence, William collaborated with Florentine ceramicist, Cantagalli, to produce some of his most ambitious holloware. Combining Cantagalli’s mastery of producing three-dimensional vases with elaborate decoration and moulding, matched with William De Morgan’s imagination for creating fantastic beasts, and bringing mythological characters to life, led to exciting ceramic productions.

Fulham Period 1888 – 1907

Sands End in Fulham was the final site of the De Morgan ceramic works before the business eventually folded, and this period was perhaps the most exciting. William had perfected his lustre glazes, had trained and developed a dedicated team to expertly turn his design ideas into reality and gone into business with architect Halsey Ricardo.

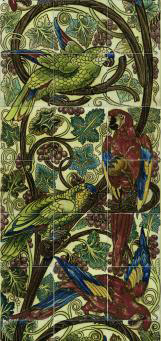

It was under Ricardo’s influence that De Morgan & Co. produced large scale pictorial tiled schemes for interiors. Whilst William had previously designed such schemes, the scale and ambition really developed whilst at Fulham. The Parrot Tile Panels were designed to repeat over 16 tiles so that entire rooms could be covered. A similar scheme can still be seen at the Tabard Inn/Pub, Chiswick, London.

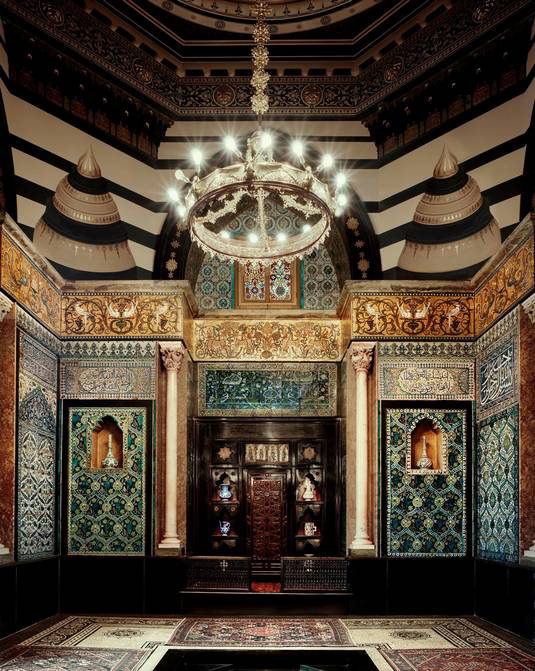

Celebrated Commissions

William De Morgan’s first major commission was to install Frederick, later Lord, Leighton’s collection of Damascan and Iranian tiles into the ‘Arab Hall’ extension of his Holland Park home, from 1877 – 1881. This was pivotal in his career as it first exposed him to the original Middle Eastern designs which he would adapt and use throughout the rest of his career as a designer. Working under the celebrated architect George Aitchison and for Frederick Leighton, the notable painter and president of the Royal Academy of Arts grew. William’s reputation as a first class tile designer.

It was because of the fame William received from the Leighton commission, that in 1880 the Czar of Russia’s yacht-building team commissioned William to design a Middle-Eastern inspired scheme for the opulent saloon of the infamous Livadia, an experimental yacht which only sailed once before being decommissioned on account of the excessive damage her novel wide bottom was susceptible to from wave slamming during transit.

Between 1882 and 1900, William De Morgan designed tiles for twelve P&O Ocean Liners, having been approached by Arts and Crafts architect T.E. Collcutt who was responsible for designing these floating hotels. By the 1880’s steamships had become a popular and luxurious way to travel and De Morgan’s exotic and elaborate tile designs were perfect for the sumptuous interiors that P&O sought to provide for their passengers.

The De Morgan Foundation acquired this spectacular galleon panel at auction on the 4th October 2006 (Sotheby’s Lot No.6) with the generous assistance of The Heritage Lottery Fund, The Art Fund and Mr John Scott. Measuring 2ft by 5ft, the panel consists of 40, 6 inch square tiles and represents a colourful and exotic scene of sailing ships, birds and sea creatures. The panel was probably produced as a test for a technique of transferring the design to the tiles.

We have now got the method of papering the glass so perfect that a better palette would give a most enviable way of painting. The paper on the glass in now so hard that we can draw on it in pencil and rub out even with India-rubber, and when an accident does occur any space can be cut out and refilled to a nicety. It’s very pretty!

Described by William in a letter to his business partner Halsey Ricardo in 1895: after using the glass to help transfer the pattern from the master design to paper, pigments would be applied and the painted paper then placed face down onto slip-coated tiles, coated with glaze and sodium silicate and fired. The paper would turn into fine ash and be easily absorbed in the glaze. Looking closely at the tile panel, we can see lines where the tracing papers join together. These aren’t as apparent on later panels and thus we can assume that the galleon panel was an early example of this technique and still in need of perfecting in 1895.

William De Morgan’s last commission came from his friend, the artist G. F. Watts, who had designed a monument to commemorate those killed whilst trying to save others in ordinary acts of heroism. His ‘Monument to Heroic Self Sacrifice’ still exists at Postman’s Park in the City of London. William designed and made ceramic plaques listing the names and acts of those Watts deemed worthy of inclusion. William made the last batch of tiles for the monument in 1905, the refused further commissions due to the termination of his business. Subsequent orders were fulfilled by Doulton’s of Lambeth.

The Passenger Brothers and Bushey Heath

In 1922, Ida Perrin, a collector of De Morgan ceramics and major donor to Leighton House Museum, called upon two of William De Morgan’s most trusted workers, brothers Fred and Charles Passenger, to continue to create the pottery they had been making for WIlliam De Morgan at a new site in Bushey, North London. They used their skill and knowledge gained from over 60 years combined experience in working for William De Morgan as potters, kilnmasters and decorators to make some exquisite pottery. The De Morgan Foundation recently acquired two pieces of Bushey Heath Pottery in order to represent the impact of De Morgan designs on future generations of artists.

A Successful Second Career

I know of a great many quarters that would believe in D.M. & Co. if D.M. were to be kept in a sort of aesthetic pound and not allowed to meddle with the ledgers…

William De Morgan in a letter to Reginald Blunt, reproduced in ‘The Wonderful Village’ (1918)

By 1904, William De Morgan’s ceramic career was essentially over. He had always focussed his abundant energy into making beautiful and technically perfect ceramics, too wrapped up in the excitement of the kilns and lustre glazes to worry about finances or fashions. The pottery had survived for 30 years but eventually, the struggling business, combined with a change in taste towards the clean lines and muted palettes of art nouveau at the turn of the century, left De Morgan & Co with no option but to close. William gave his blessing to the Passenger Brothers, his trusted staff Fred and Charles, to carry on creating De Morgan designs which they worked on and sold from a Brompton Road showroom in Kensington, London, until the business closed permanently in 1907.

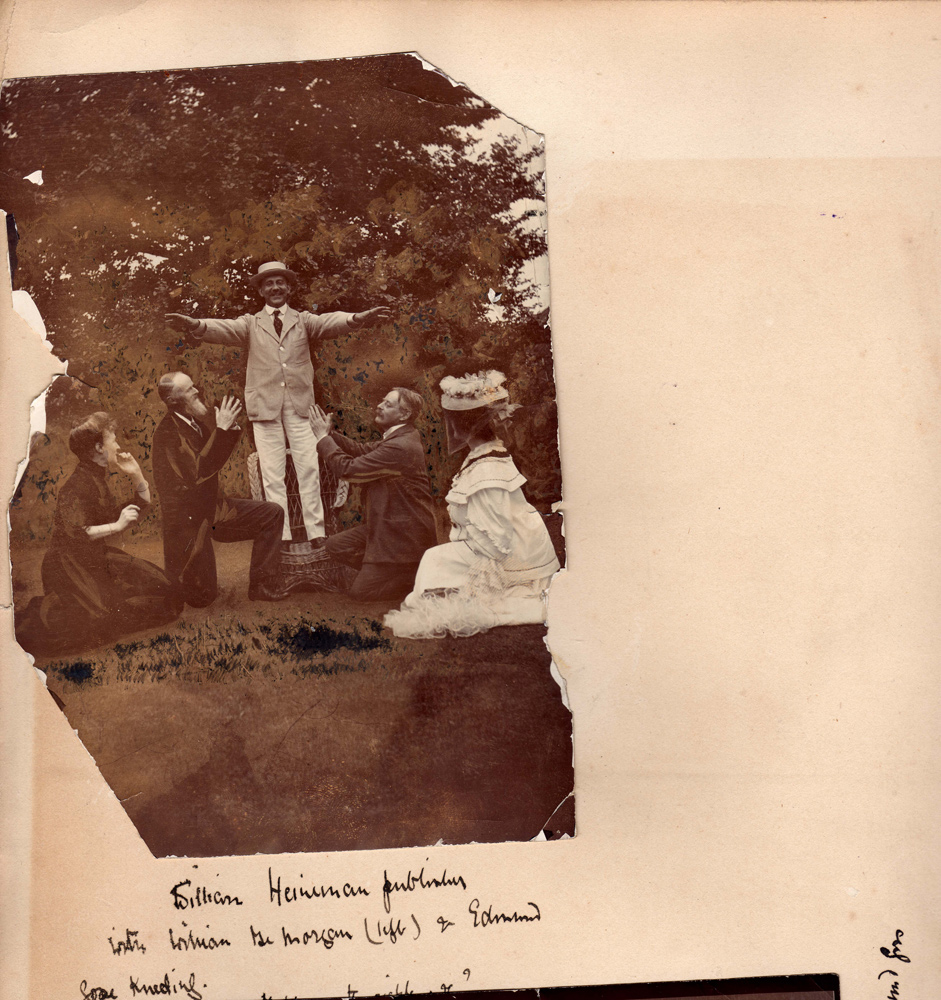

William De Morgan kneels and claps at William Heinemann, with his arms outstretched, in this fun group shot.

This brought on a bout of depression for William De Morgan. Having been a creative and a business owner for his entire adult life, the adjustment to enforced retirement must have been difficult. With the support of his wife, Evelyn, he began writing fiction. His first novel, the semi-autobiographical Joseph Vance, was published in 1906 by William Heinemann and was a huge international success. William went on to write seven novels and made his fortune in doing so.

William passed away in 1917, after contracting trench fever from a visitor to the house. He was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, in Surrey, in a grave designed by Evelyn De Morgan.

Donate

We rely on your generous support to care for and display this wonderful collection