What can we discover about artists from the materials they bought? William and Evelyn De Morgan both shopped for art supplies at Charles Roberson, a leading ‘colourman’ (art material merchant) of the Victorian period. Art historian, Fiona Mann, has kindly transcribed William and Evelyn’s pages in Roberson’s thorough sales ledges for us. What she has found give much insight into the artists’ lives and careers.

William and Evelyn De Morgan’s purchases from Charles Roberson, colourman,

1861 to 1919

Over a period of some fifty years, William De Morgan purchased materials from the major artists’ colourman, Charles Roberson, who by 1861, were established at premises in Long Acre, in London. The ledgers, which I have recently transcribed, and which be available to readers on request, are both detailed and illuminating. They provide a clear insight into the changes in artistic direction experienced by De Morgan: from his early years of drawing and painting, starting in 1861, to his period of stained glass designing, then to his years of ceramics production. They also include several separate ledgers for his wife, the artist Evelyn Pickering, whom he married in 1887, although close analysis of William’s entries suggests he was buying materials on Evelyn’s behalf, too, with regular orders for canvas supports, oil paints and brushes long after he had stopped painting pictures himself.

During the period, not only do the materials ordered by De Morgan alter, but they reflect changes of address, as he moved both his home and factory premises around the rapidly urbanising London area, to accommodate his developing personal and business requirements. The ledgers are equally instructive by the omissions they contain – regular gaps in orders are noticeable over the winter months, particularly between 1893 and 1914, when, seeking to alleviate William’s debilitating back problems, William and Evelyn departed for the more clement temperatures of Italy. From there William supervised factory production of his ceramics and tiles back in England, as well as continuing to design. Evelyn appears to have been very productive, too, during her months in Italy, finally bringing back many completed canvases on their final return to England in 1914. During their stay abroad, it is probable that they acquired additional materials from local Italian suppliers.

Early ledgers 1861 – 1870

[MS 104-1993-232; MS 105-1993-130; MS 106-1993-10a; MS 107-1993-109; MS 108-1993-100]*

William De Morgan attended Carey’s School of Art (the address used for his first order in 1861), but, on leaving, considering himself ‘a feeble and discursive dabbler in picture-making, I transferred myself to stained-glass window-making, and dabbled in that too till 1872.’

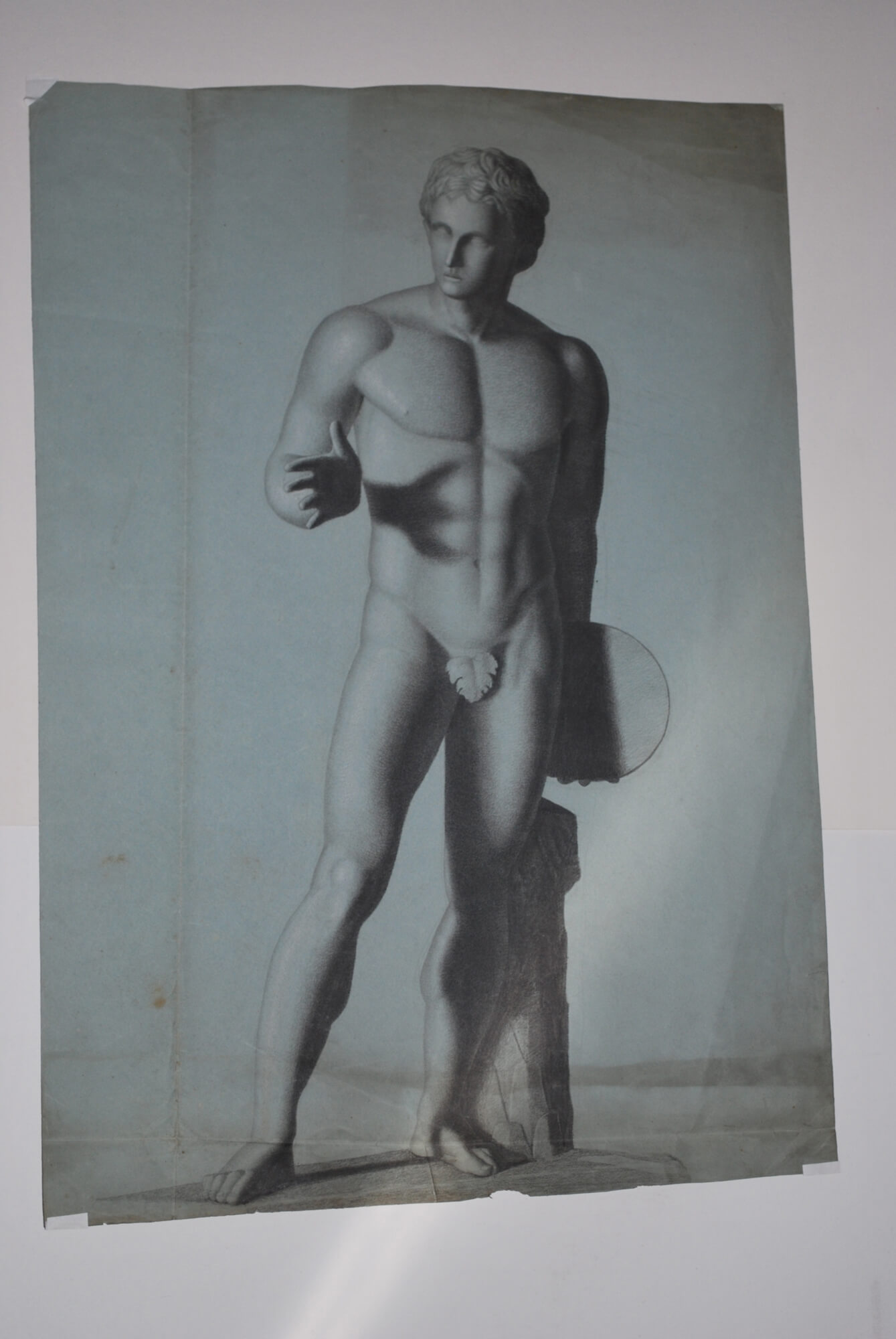

Study from the Antique Cast, a Drawing by William De Morgan made at Cary’s (left)

His orders during this period relate predominantly to materials for sketching in chalk, charcoal, pencil, ink and watercolour, using moist pigments such as Van Dyke Brown, Raw Umber, Vermilion and shell gold, as well as sable and camel hair brushes. There are increasing orders for pieces of Cartoon paper mounted on linen or for yards of Cartoon paper, on which he would produce his designs for the various stained glass commissions he worked on, both for Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, & Co. and also in conjunction with J. T. Lyon & Co, of 40 Fitzroy Square. [Incidentally, this is one of the addresses featuring in orders between 1868 and 1870 (MSS 107 and 108)]. Ever experimental and curious about techniques and materials, De Morgan strove to produce luminous colour combinations under the guidance of Lyon, setting up a kiln in the cellar of his house to facilitate his attempts. The De Morgan Foundation archive contains a number of examples of De Morgan’s stained glass window designs, including one for an Old Testament King, 1865 (pictured below) and two beautiful watercolour designs of The Prodigal Son and Moses & Christ of around the same time. William Waters’ book, Saints & Symbols: Pre-Raphaelite Stained Glass, includes full colour photographs of some of the actual windows made from his designs.

Indicative of De Morgan’s fascination with different techniques is an order in August 1864 for a small block of box wood, traditionally used for creating intricate wood engravings, so it is possible he was experimenting at this time with designs of this kind. He would return to work in this medium in 1880, when the ledgers show an order for two wooden blocks in April and another two in May. His interest in line illustrations can be seen from the numerous black and white compositions he created to accompany his sister, Mary’s, book of children’s fairytales, On a Pincushion, published in 1877. These engravings were apparently made in an unconventional manner, not on boxwood, but by scratching through a white paste applied to sheets of windowglass.

While De Morgan had quickly abandoned the medium of oil painting, the ledgers provide evidence that he continued to buy small panel supports for oil painting in 1869 and 1870 [MSS 107 and 108], although these dimensions do not correspond to any finished works by the artist which are known today. Two surviving framed pictures from this early period are portraits, one of Millicent De Morgan and the other a self-portrait, both of which are in the De Morgan Collection.

Ledgers 1875-1890 [William De Morgan and Miss Pickering/Mrs De Morgan]

[MS 109-1993-182; MS 109-1993-190; MS 109-1993-175; MS 110-1993-174; MS 110-1993-449]

In 1872, William De Morgan moved to No 30 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, where he established a kiln and began a new phase of his life, producing pottery.

Initially he worked on tile production, employing a number of young women to paint his designs onto the tiles, and developing a process for recreating beautiful lusterware products.

While up to 1881 he continued to order a few lengths of Cartoon paper, possibly for later stained glass designs, the ledgers for the period 1875-1883 are mainly filled with orders for camel hair brushes and large numbers of Crow, Duck or Goose sable writers. These are brushes of small to medium size (Crow being the smallest) made from long sable hairs which seem to have first appeared on the market during the later years of the nineteenth century. Still available from the supplier Cornelissen today, they are said to hold large amounts of colour and to be used for painting long lines and detail. It is to be supposed that they were used for painting his designs onto tiles and pots. Maybe some were purchased for the use of the painters he employed. In January 1876 [MS 109-182] he bought 7 ½ dozen Crow Sable Liners. A post-1881 Roberson catalogue lists Crow sable writers at 3 shillings per dozen and duck writers at 6 shillings per dozen, so it is clear William was often ordering the brushes by the dozen. The Victoria & Albert Museum holds a wide variety of his intricate watercolour designs for ceramic tiles, dishes and vases, meticulously painted using such brushes. Apart from brushes, the ledgers for these dates mainly contain items such as sketchbooks, moist watercolours, and one order (in June 1875) for a silverpoint together with six sheets of suitably prepared silverpoint paper. Metalpoint was an art which was undergoing a renaissance towards the end of the nineteenth century, practiced by artists such as his friend, Edward Burne-Jones, who experimented with the technique from around 1879. Special metalpoint papers could be acquired from colourmen, such as Charles Roberson and T.J. & J. Smith. Burne-Jones is also known to have used a tinted paper from the French manufacturer, Canson and Montgolfier, and in March 1882 De Morgan also requested sheets of Canson paper from Roberson. It was said to be a hard-sized paper which was particularly suitable for chalk drawing, and has also been identified as the support used for two of Evelyn De Morgan’s luminous gold drawings, including Gloria in Excelsis of 1893 [De Morgan Collection].

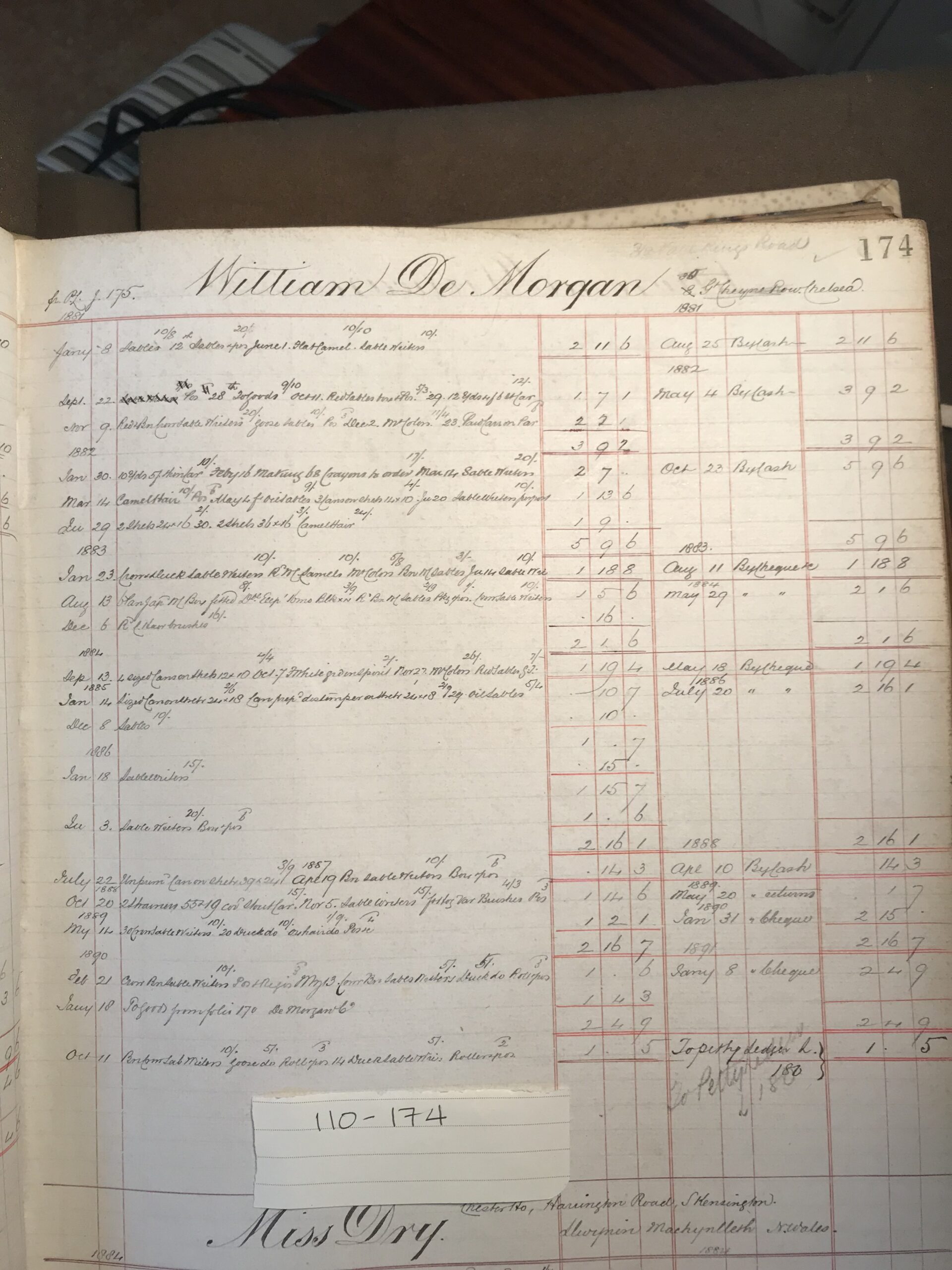

There is an interesting order in January 1882 for 68 crayons made to order [MS 110-174] at the same time as 10 yards of 5 foot wide Cartoon paper. It does not specify the colour of the crayons, which must have been different to the chalks or the Conté crayons which De Morgan regularly ordered from 1866 [Contés were traditionally only available in three colours: black, white, or red]. A hand-annotated Roberson price catalogue from around 1909 in the Hamilton Kerr Institute lists Roberson’s own ‘chalks, crayons, etc. for drawing’ and also ‘Cartoon Chalks’, available in a range of colours, including ‘scarlet, purple, crimson and green’ [HKI 869-1993]. It is not clear what De Morgan would have been using such large quantities of these crayons for at this time, although in 1882 he received his first commission for designs for large decorative tile panels from the Peninsular and Orient Steam Navigation Co. (P&O), which may have been sketched out using crayon on sections of cartoon paper.

After 1884, however, there is a distinct change in the content of the ledgers, starting with MS 110-174. Alongside regular items such as sable and camel hair brushes, we find a number of canvas supports on stretchers, ranging in dimension from 12 x 10 inches to 39 x 24 inches. One canvas support listed in January 1885 is specifically to be prepared with distemper. In 1883, De Morgan had met the talented artist, Evelyn Pickering, to whom he became engaged in 1885. Her own separate Roberson account [MS 110-449, discussed below] dates from 1884, when it includes similar orders for ‘4 distemper canvasses’ as well as one canvas ‘prepared gesso ground on size’, in addition to other canvas-covered strainers and stretchers of increasing size. It may be, then, that following their meeting, De Morgan began placing orders on his account for Evelyn’s materials alongside his own, as he is not known to have returned to oil painting in these later years. Evelyn’s circular painting of Medusa, which is in the De Morgan Collection, and dated 1873-1885, is described as being ‘gesso on panel with bodycolour’, confirming this as a type of experimental support she employed. In fact, it seems that here Evelyn was attempting to recreate ancient methods, rather than trying to do something new. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it was standard practice to prime a canvas with gesso, and it was a process described by Cennino Cennini in his fifteenth-century treatise Il Libro dell’Arte, a work which had been translated into English by Mrs Merrifield in 1844 and was eagerly devoured by many leading Victorian artists and architects. During the second half of the nineteenth century, there was a widespread fascination with ancient techniques and a thirst for the revival of lost methods for creating illuminated manuscripts, stained glass and metalpoint, for example. The De Morgans and their artist friends were part of this wider movement.

Small quantities of paint are included in her 1886 order, mainly consisting of Antwerp Blue and Yellow Ochre, supplied as powdered pigments and priced per ounce, rather than being supplied ready prepared in tubes. The ledgers show that Evelyn continued purchasing colours in powdered form right up to her death in 1919.

Evelyn De Morgan’s own account for 1884-1890 [MS 110-449] lists a very small number of items placed almost biannually between April and December (when the two artists departed to spend their winters in Florence). They are mainly orders for canvases on stretchers of different dimensions, one 7 feet by 4 feet 4 inches, together with some pigments, chalks and sketch books. A preparatory cartoon of the large 7 foot work must have been produced on the similarly sized stretcher covered in linen and cartoon paper, which was ordered on 13 April of the same year. To date, I have not been able to establish which painting was executed on this large support. The type of canvas requested by Evelyn at this time is generally ‘Roman’ canvas, which was made with a coarser grain and was generally considered more suitable for larger paintings, as the paint was said to spread more easily on the coarser weave. Her works were regularly exhibited at the fashionable Grosvenor Gallery.

Original Ledger (Hamilton Kerr Institute)

In August 1884 Evelyn placed an order for ‘2 oval Xylonite Palettes’ costing 21 shillings. Xylonite was the first artificially made commercial plastic and was a relatively new material, with the British Xylonite Company being formed in 1877. Presumably these plastic items were much lighter in weight and thus more portable than traditional wooden palettes.

Ledgers 1891-1919

[MS 121-180; MS 121-171; MS 121-291; MS 133-193-4a; MS 133-193-4b; MS 110-449]

Following their marriage in 1887 William and Evelyn De Morgan moved to a new home in the Vale, Chelsea. While tile-making still formed a major part of the business, much of the painting for this was increasingly done by artists in Italy. During the following years, as William’s pottery business suffered financial ups and downs, Evelyn injected her own capital into it without hesitation. In the same way, William’s ledgers during this period indicate his support of his wife’s endeavours, with many orders for large pieces of canvas and canvas supports filling the pages, together with others for oil colours, hog brushes and other materials for oil painting. Between 1891 and 1898, for example, there are over sixteen orders for yards of canvas or for stretchers with canvas mounted over them. These are interspersed with more modest orders for the crow and duck sable writers constantly required by William for his tile and pottery designs, alongside moist watercolours and vibrant pigments such as Genuine Ultramarine, Cobalt, Cadmium and Gold. Cakes of gold will continue to feature in later years and will be discussed in the next section. Two ledgers, MS 121-171 and MS 121-180, contain the heading, ‘Factory Account’, and the entries in these confirm the ongoing requirement for duck, crow and goose sable writers for his factory.

From a technical point of view, it is of interest to note that from 1897 Amber colours began to appear in the ledgers [MS 121-171], presumably being employed at that point by Evelyn in her paintings. A Roberson catalogue from 1909 indicates that ‘Amber Colours for Oil Painting’ have become increasingly popular and that:

the present demand for Colours prepared with Amber has induced Messrs. Roberson to devote particular attention to that vehicle. These Colours can be confidently recommended, and are used by many of the more prominent French artists. They are ground with a special preparation of Amber, the particles of colour being locked up in the vehicle, with the result of greatly increasing the permanency of the pigments. They dry more thoroughly and from below instead of forming a skin on the surface, and are much more brilliant than when ground with oil alone. They are of a very pleasing consistency for work, being stiff and solid on the palette, but yielding freely under the brush or knife.

They were supplied in ‘wide-mouth Double Tubes’ and were priced according to six series of colours, from 8d each to 4 shillings and 6d each (for Crimson Madder and Ultramarine Grey). Amber Medium was sold for use with the colours, priced from 1 shilling and 3d an ounce.

In October 1897 Evelyn De Morgan appears to have also purchased Pale Amber Varnish, another product of increasing popularity during the later years of the 19th century, although it was not recommended as a final varnish layer because of its dark colour. The ledgers show her still purchasing Pale Amber Varnish as late as July 1912 [MS 110-4490]. Evelyn’s use of Amber colours may reflect an interest in their reputed brilliancy, a subject which had also fascinated William during the 1870s, when he experimented with glycerine as a medium in oil painting to produce ‘a remarkable richness of colouring.’ Evelyn’s experimental approach is further reflected in the purchase in June and July 1902 of canvases ‘prepared paraffin wax & plaster of Paris full SP [single-primed] surface on stretcher’ [MS 133-193-4a]. These appear to have been specially prepared by Roberson, who notes in August 1902: ‘Specially preparing piece of open Canvas with paraffin wax at back & plaster of Paris ground surface & experiments with same & straining on stretcher 36 x 34’. It would be interesting to trace the works which were created on such innovative supports.

Another product appearing in the ledgers from 1900 is ‘Ferraguti’, a fixative made by the French colourman, LeFranc & Cie, who supplied Roberson with products such as pastels, from 1880. While Roberson made their own fixative, and Burne-Jones often chose another French product, Rouget’s Fixative, which had been widely publicised from 1870, it is indicative of her experimental character and of her knowledge of European artists’ materials, that Evelyn preferred this less well-known product. Fixative was traditionally used for chalk and charcoal drawings to prevent them smudging. She was presumably ordering the Ferraguti product for her preparatory pastel drawings, such as the two preparatory chalk drawings on brown paper for The Cadence of Autumn, which are in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Between 1902 and 1915, orders for the Ferrugati fixative appear regularly in the Roberson ledgers. Perhaps William De Morgan also adopted this fixative to stabilise his own designs.

One item which regularly features in the De Morgan ledgers between 1903 and 1906, as well as in 1897 and 1898, is cakes of gold. In 1903 and 1904 the orders are specifically for cakes of ‘red gold’, costing over 4 shillings. The De Morgans were close friends of the artist Edward Burne-Jones, who, from 1861 had been incorporating gold into his watercolour paintings. Between 1893 and 1896 he is known to have purchased cakes of red, lemon and green gold from Roberson, as well as cakes of silver and aluminium, to create experimental luminous effects. This signalled a time when watercolour had, somewhat controversially, developed into a medium used for highly decorative and visual purposes. Evelyn De Morgan considered that gold had a further significance, believing it to have a spiritual dimension and representing the colour of salvation. This is evident in a number of the beautiful gold drawings on dark grey paper which she painted between around 1884 and 1902, including the stunning Gloria in Excelsis [De Morgan Collection]. Seven of her gold drawings were exhibited at the Fine Art Society in 1889.

In 1907, after many financial struggles, William De Morgan finally and reluctantly closed his ceramics business, turning to writing and producing several highly successful novels. The couple left Florence for good in 1914. Returning to live permanently in England, it is noticeable that William De Morgan’s orders from Roberson are reduced to a trickle, finally stopping after June 1915. Evelyn’s paintings were all packed up in Florence and sent back to their new home in Church Street, Chelsea, while William continued to work at his novels. Despite William’s death in January 1917, Evelyn’s final ledger [MS 110-190] shows she continued to order a few colours, brushes and one No. 9 canvas that year.

Evelyn continued to purchase a small number of products from Roberson [MS 110-190] over the following years, mainly powder colours and the expensive genuine ultramarine, costing 21 shillings, as well as brushes and several medium sized canvases. Her final order, on 28 April 1919, for a Roman Canvas, was placed only days before she died.

Fiona Mann 2024

*refers to the archive reference number of the Ledgers in the Hamilton Kerr Institute, Cambridge