Review

Evelyn De Morgan: The Gold Drawings

In October 2022 Leighton House in London reopened its doors, following the completion of its £8m renovation. Located downstairs from the main house is the fully refurbished new wing with its Tavolozza Drawings Gallery, whose current exhibition, Evelyn De Morgan: The Gold Drawings, is on display from 11 March to 1 October 2023. The humble size of the gallery provides a quiet atmosphere of reflection that not only benefits the study of De Morgan’s small-scale works – fourteen in total – but allows them to shine without distraction.

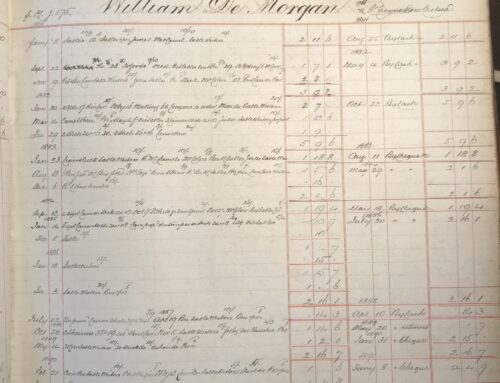

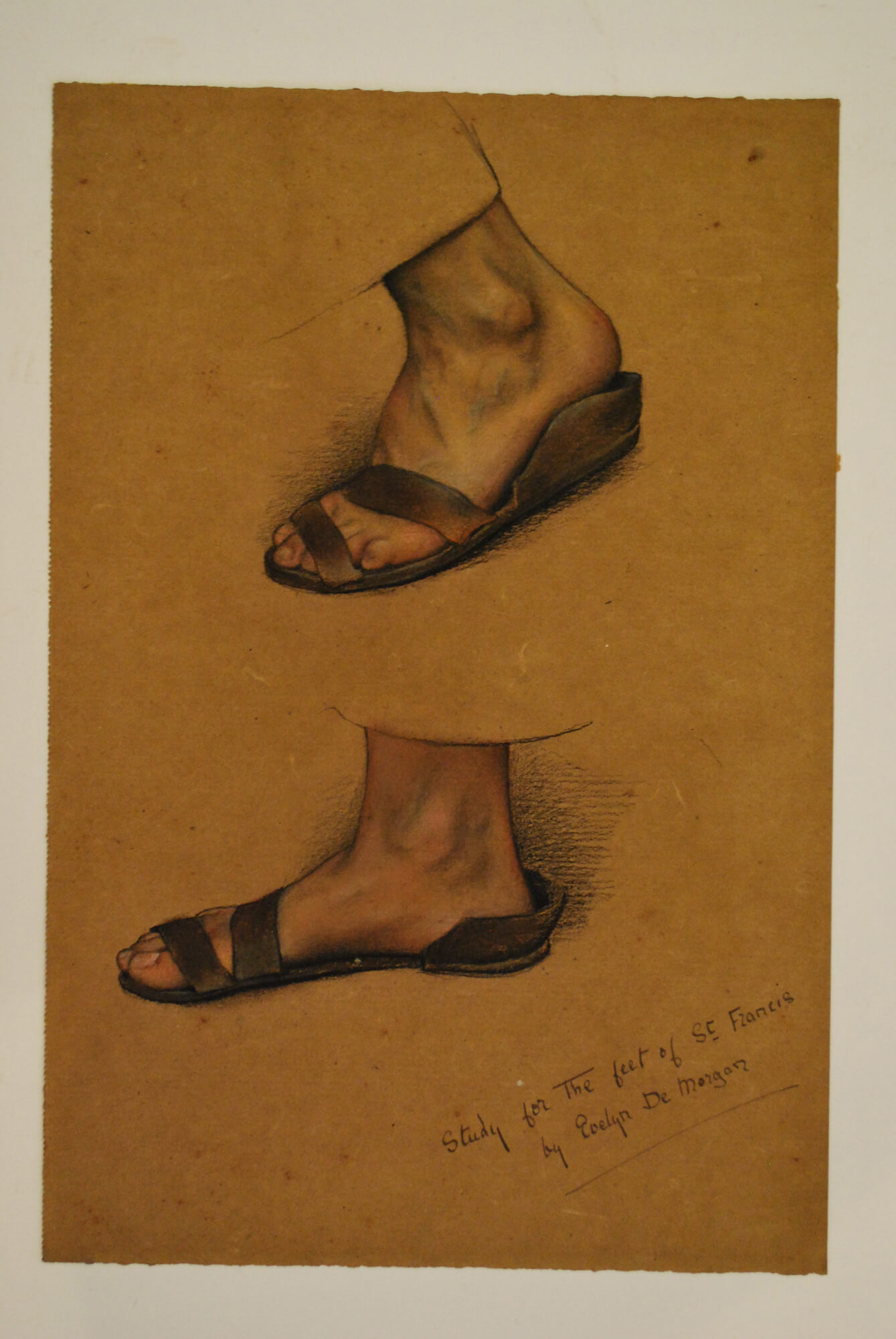

Upon entry to this intimate space, we are introduced to the subject of the exhibition and encouraged to take stock of the artist’s accomplishments and excellence. We are told that Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) was not only accepted to study at the Slade School of Art in 1873 but was awarded a scholarship by the school the following year: one of the first women accorded this prestigious honour. Upon commencing her career as a professional artist, De Morgan excelled in a range of media, even inventing her own artistic tools and materials; the gold paint and crayons – created from ground-up dry pellets of gold pigment – used in the creation of a number of the drawings on display were De Morgan’s own invention. The exhibition makes it clear that she was an intelligent and methodical draughtsperson, producing numerous sketches and studies ahead of commitment to a final composition. This is evidenced in the first four works in the exhibition showing three studies for The Marriage of St. Francis and Holy Poverty alongside the fully realised composition in gold and chalk.

Study in Chalk of the Feet of St Francis

Through clever curation, De Morgan’s development of visual forms is further explored in the fifth work in the show, a gold version of The Marriage of Boreas and Oreithyia that predates the artist’s later painting of the same name. Through its label and accompanying illustration, the visitor is encouraged to not only compare the two versions of this composition but to consider the material qualities of the media and their relationship to the subject. In both images, the winged god Boreas (the personification of the North Wind) gently supports Oreithyia as the pair fly above seas and mountains. However, in the painted version, De Morgan emphasises the weightless quality of her two figures, contrasting the serenity and gentleness of the pair’s frozen poses as they float in the air with the frenzied, swirling activity of the looping drapery that surrounds them. Boreas’s hands hover over his bride’s body without actually touching her, their physical connection instead limited to the placement of Oreithyia’s wrist upon her beloved’s forearm and the proximity of her back to Boreas’s torso; their gazes are likewise unconnected. However, where the painting of The Marriage of Boreas and Oreithyia carries the coolness of the North Wind air, the drawn version in this exhibition is warm and intimate. Boreas’s fingertips now gently caress Oreithyia’s chest and elbow. The pair turn in towards one another, with the windswept drapery now wrapped closer around their bodies as if it were a cocoon or, perhaps more intimately, a set of tousled bed sheets. This quality is expressed through De Morgan’s careful handling of her chosen medium, with fabric and skin delicately differentiated through sharp and soft applications of line and pigment. Where the sunlight reflects off the peaks of the mountains in the distance, the viewer is encouraged to read Boreas and Oreithyia as similarly clothed in the light of the sun through the limited palette of this golden drawing. The presence of this work in the exhibition not only encourages the viewer to reflect upon De Morgan’s practice of pictorial evaluation and development of a single composition but to consider her ability to adapt her pictures according to the qualities and attributes of her medium.

- Boreas and Oreithyia in Gold

- Boreas and Oreithyia, 1896 (oil on canvas)

The accompanying wall text throughout the show – written with an expert balance of clarity and detail – also encourages visitors to consider the transformative nature of De Morgan’s choice of medium, with the materiality of the artworks playing just as an important part of the show as the pictorial schemes themselves. For example, through comparisons with artistic methods of fresco painting and sculpture, the visitor is encouraged to reflect upon the three-dimensional quality present in the physical construction of layered pigments in these flat images. Looking at De Morgan’s intricate depiction of holy light in Mercy and Truth and The Valley of Shadows, I was also inclined to consider the artist’s possible use of sculptural forms as pictorial inspiration; the delicate lines of bright light in these two drawings recall the three-dimensional golden rays in Bernini’s sculpture The Ecstasy of St Teresa, located in Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, which the artist could have seen for herself on one of her many trips to Italy.

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa (1675)

- Evelyn De Morgan, The Valley of Shadows (c.1890)

- Andrea Mantegna, The Introduction of the Cult of Cybele at Rome (1505-6)

This connection is perhaps unsurprising given the exhibition’s keenness to foreground De Morgan’s artistic practice within the legacy of Italian Renaissance masters, such as Giotto and Mantegna. This focus is refreshing in its avoidance of well-trodden comparisons of De Morgan’s work with Edward Burne-Jones and other contemporary artists involved in second and third generation Pre-Raphaelitism. Instead, the exhibition emphasises the historical grounding of De Morgan’s work and the sense of her keen academic study embedded within her innovative designs and techniques, providing a sense of reverence and dialogue with the past within the artist’s works.

The exhibition also makes a point of highlighting the practical and spiritual elements at play in De Morgan’s use of gold in these drawings, as both commercially available physical artist’s pigment and as a colour weighted with both spiritual and personal significance. For De Morgan, gold was the colour of spiritual salvation. As such, her application of this colour within the show’s various biblical and mythological pictures carries a deeper purpose, not only elevating the sense of power and holiness possessed by her subjects but communicating the sense that these drawings could provide both a meditative and transformational service for both their creator and viewer alike. As such, through the visitor’s encounter with the golden rays of light in Mercy and Truth and The Valley of Shadows, one might also perceive De Morgan’s use of luminous pigment as the artist’s attempt to clothe the viewer in the same golden light of spiritual salvation.

Much like in alchemical transmutation, with attempts to convert base elements into gold, this exhibition focuses on the transformational qualities at play in its subject, emphasising De Morgan’s inventive and versatile artistic capabilities. Likewise, the artwork on display actively engages with the interplay of the material and ethereal, the physical and spiritual, to create images of peace, connection, and reverence: a sense that is heightened through the intimacy of the space. This little jewel of an exhibition, tucked away beneath Leighton House, will resonate with visitors far beyond the initial luminosity of its golden subjects.

Susie Beckham, University of York