William and Evelyn De Morgan both benefitted from a formal art education in the late-Victorian period. At this time, instructing young artists in drawing from the antique cast was considered the pinnacle of artistic instruction.

Collectors in England have long been fascinated with the ancient world. In the Victorian period, this antiquarian interest in world architecture and sculpture peaked just as many new museums were being established. This led to a burgeoning market for reproductions – or copies – of outstanding national monuments and notable sculptures. Plaster casts were the quickest and easiest option for making antique sculpture widely available, and the casts even became revered objects in their own right.

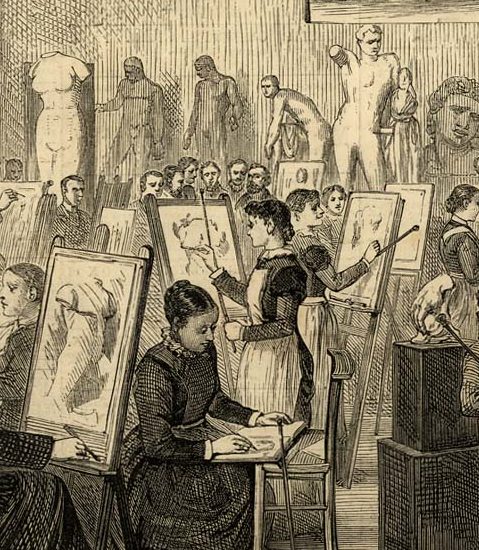

Evelyn De Morgan attended the Slade School of Art, and William the Royal Academy Schools. Both of these establishments has ‘Antique Rooms’ where art students would work on copying casts of ancient sculpture in order to learn principals drawing, such as the human form and anatomy, classical proportions and linear perspective.

Antique Room at the Slade School of Art c.1880

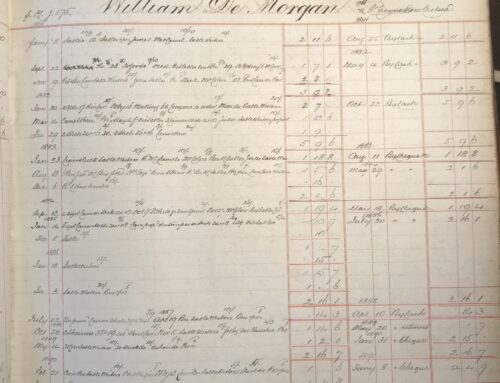

William De Morgan began his work in copying from the antique cast when he was about 19 years old and had decided to become an artist. He trained with Cary at his specialist school in teaching academy hopefuls, following in the footsteps of John Everett Millais to do so. De Morgan excelled and soon began at the Royal Academy Schools in 1859.

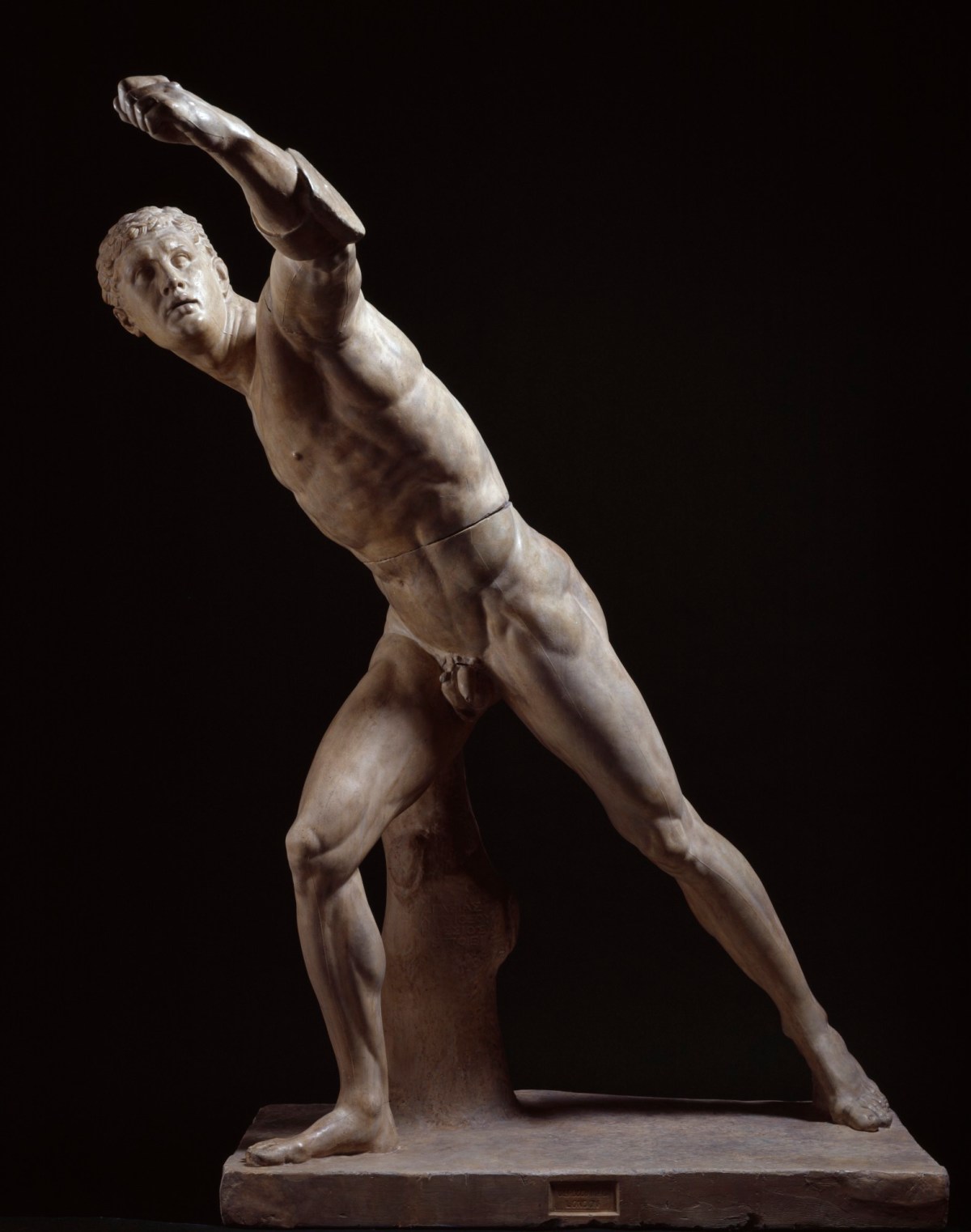

Cast of the Borghese Gladiator, ?late 19th century. Agasias of Ephesus (b. ca. 75 BC- ca. 25 BC)

William probably produced his copy of the Borghese Gladiator cast at the Royal Academy Schools. This cast is still in the Royal Academy Collection today. This cast is a plaster cast made from a marble statue found at Nettuno near Anzio in 1611. It was in the Borghese collection by 1613 (hence the name by which it is commonly known, the Borghese Gladiator), and was the most admired of all the ancient sculptures in the Royal Academy collection.

William De Morgan’s drawing of the cast

A plaster cast of the Borghese Gladiator was at the Royal Academy by 1795, the year Henry Singleton painted it in his group portrait The Royal Academicians in General Assembly, pictured below.

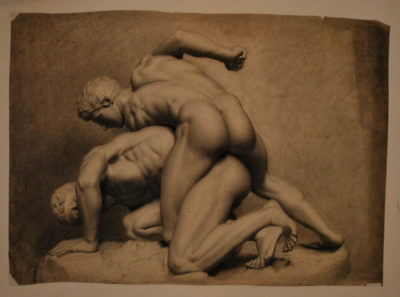

Perhaps the finest example of William De Morgan’s drawing from the antique is his Wrestlers (below). It depicts two men engaging in the pankration style of wrestling, a sporting event introduced into the Greek Olympic Games in 648 BC.

This is a plaster cast of a marble sculpture which was discovered in Rome in 1583 and is now in the Uffizi collection. It was discovered with another sculpture, the ‘Niobe Group’, and initially the two groups were thought to have belonged together. Soon after the discovery of the two groups they were bought by Cardinal Ferdinando de’Medici, and they were installed in the Villa Medici in Rome by 1594. The Wrestlers was sent to Florence in August 1677, and was positioned in the Tribuna of the Uffizi by 1688.

William’s drawing is highly accurate, and the piece demonstrates his clear ability to use ratio and perspective to great effect. His control of the rendering allows him to express the depth and presence of the sculpture. Although William did not continue to create artworks featuring the human form later into his career with ceramics, this piece shows him to have been an able and accomplished student.

But why did so much classical sculpture feature sports and games? According to tradition, the most important athletic competitions were inaugurated in 776 B.C. at Olympia in the Peloponnesos. These ‘Olympic Games’ are of course still celebrated today. The games were held in dedication to the Gods, making them an essential part of ancient Greek life. Much like we do today, the ancient Greeks looked forward to games which were an exciting part of the culture. They provided entertainment and a common cause for celebration. As well as the sporting element, many games included festivals, ceremonies, feasts and concerts.

Many local games, such as the Panathenaic games at Athens, were modeled on these four periodoi, or circuit games. The Pythian games at Delphi honored Apollo and included singing and drama contests; at Nemea, games were held in honor of Zeus; at Isthmia, they were celebrated for Poseidon; and at Olympia, they were dedicated to Zeus, although separate games in which young, unmarried women competed were celebrated for Hera.

The victors at all these games brought honour to themselves, their families, and their hometowns. Public honours were bestowed on them, statues were dedicated to them, and victory poems were written to commemorate their feats. Numerous vases are decorated with scenes of competitions, and the odes of Pindar celebrate a number of athletic victories. Since antiquities have been collected, many of them of course represent the games and victors which were so revered in ancient culture.

Evelyn De Morgan won various medals at the Slade School of Art for her work in copying from the antique cast. Her work in this area deeply influenced her presentation of figures in her painting as many of them have a sculptural quality. The poses and arrangement of her young, athletic figures are clearly a result of her early training.

Her painting Phosphorus and Hesperus (1881) is inspired by Greek Mythology and sculpture. It depicts the Morning star (Phosphorus) and the Evening star (Hesperus) and alludes to the circle of life. Phosphorus is rising, his torch held erect, heralding the morning which is lightening the sky behind him. In comparison Hesperus’s evening starlight is fading, as his flame in its dark torch droops and gutters, his eyes are closing, his dark head anticipating the relaxation of sleep. The stylistically flattened figures and marble tones of the young men in the painting clearly reference Evelyn’s interest in classical sculpture and the unusual representation of two nude male figures with their phallic torches caused controversy when first exhibited. However, the female hand is apparent in the painting as the seashore backdrop allowed Evelyn to imbue the image with potent female symbolism in the form of sea shells which represent female fertility and sexual potency.

Phosphorus and Hesperus (1881)