On Thursday 12th December, Evelyn De Morgan’s painting The Wandering Jew (1888) will go on sale at Christie’s in London, with a chance to view the picture from 7 – 11th December in the ‘British Art: Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art sale’ exhibition.

From extensive exhibition records, the last known instance of the picture was when it went on display at the Royal Manchester Institution in 1888, shortly after first being on display at the New Gallery in London in the same year. Until its consignment to Christie’s for this sale, the painting has been untraced and so it is a delight to see it return to public view, however briefly, ahead of the winter sale. Having the physical painting to examine has revealed that it was previously consigned to Christie’s in 1891.

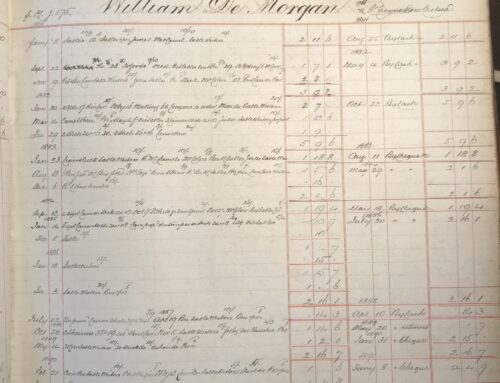

The serial number stamped on the reverse can be traced through Christie’s records to a Miss Pitcher of Acton, who may have bought the picture from the Manchester exhibition in 1888. The 1891 census shows that Miss Pitcher could have been either Augusta or Sophia, two sisters in their 70s, living in a big house called Strathreay in Avenue Gardens, in the Mill Hill area of Acton. The 1895 voters list reveals Augusta Pitcher as the freeholder of the property and so she would certainly have had the means to buy her own paintings and decide to put the picture for sale in 1891.

The painting didn’t find a buyer in the 1891 sale, and so how it ended up with the present vendor in the USA by 1970 is still a mystery.

The Wandering Jew, according to the legend, mocked Christ as he carried the Cross to Calvary and was sentenced to an immortal life wandering the earth in repentance. De Morgan has taken this legendary figure, and used it as a symbolic motif for the entrapment of the mortal soul in the human body.

Apparently, any religious or narrative presentation of the subject was irrelevant to De Morgan, as it is the shrouded body of a young woman on a bier which dominates the composition. Her delicate auburn hair, bone white skin, and cold blue lips are arresting, instantly telling of her recent passing. She is directly contrasted to the wandering Jew dressed in deep purple robes, with a long white beard and gnarled hands, who looks sorrowfully over her corpse.

When De Morgan met William in 1883, she began to take a deep interest in Spiritualism, encouraged by her mother-in-law Sophia De Morgan who was a practicing medium. From this time, she began to paint more overtly Spiritualist subjects which deal with the emancipation of the human soul upon death. The Wandering Jew is such a painting. By contrasting the weary, elderly man with the deceased young woman, she makes her case that there is more sorrow in immortality than in the passing of youth, who will never live to see the sorrows of life on earth.

The picture is full of rich symbolism to enforce this view. Behind the young corpse is an open window which looks out over a serene Italianate landscape. Perched between the claustrophobic emerald marble hall where the body lies and freedom outside, is a dove which patiently waits on the windowsill to take flight. Traditionally an emblem of peace, the dove represents the passing of the human soul from entrapment to freedom as it takes flight from the body.

When the picture was first exhibited, it had the subtitle ‘whom the gods love die young’ taken from Byron’s poem Don Juan, which attempts to reconcile grief felt at the passing of youth by celebrating the departed being at peace.

‘Whom the gods love die young’ was said of yore

And many deaths do they escape by this:

The death of friends and that which slays even more

The death of friendship, love, youth, all that is,

Except mere breath. And since the silent shore

Awaits at last even those whom longest miss

The old archer’s shafts, perhaps the early grave,

Which men weep over, may be meant to save’

It is clear that this poem was crucial in informing De Morgan’s depiction of the Wandering Jew.

The painting is a true masterpiece by the artist, demonstrating her ability to invite the viewer into her composition and feel part of the narrative. The composition was clearly one she thought carefully about, taking great pains to perfect the figures in the painting. The Foundation has a preparatory study in its collection, which shows the artist’s attention to detail in rendering the drapery and ensuring the realism of the figures, making for an engaging painting.

The painting will be exhibited at Christie’s 8 King St, St. James’s, London SW1Y 6QT from 7th to 11th December and is well worth a visit.

Sarah

De Morgan Curator

With special thanks to Val Bott for researching the lives of the Pitcher Sisters and contributing to the blog.