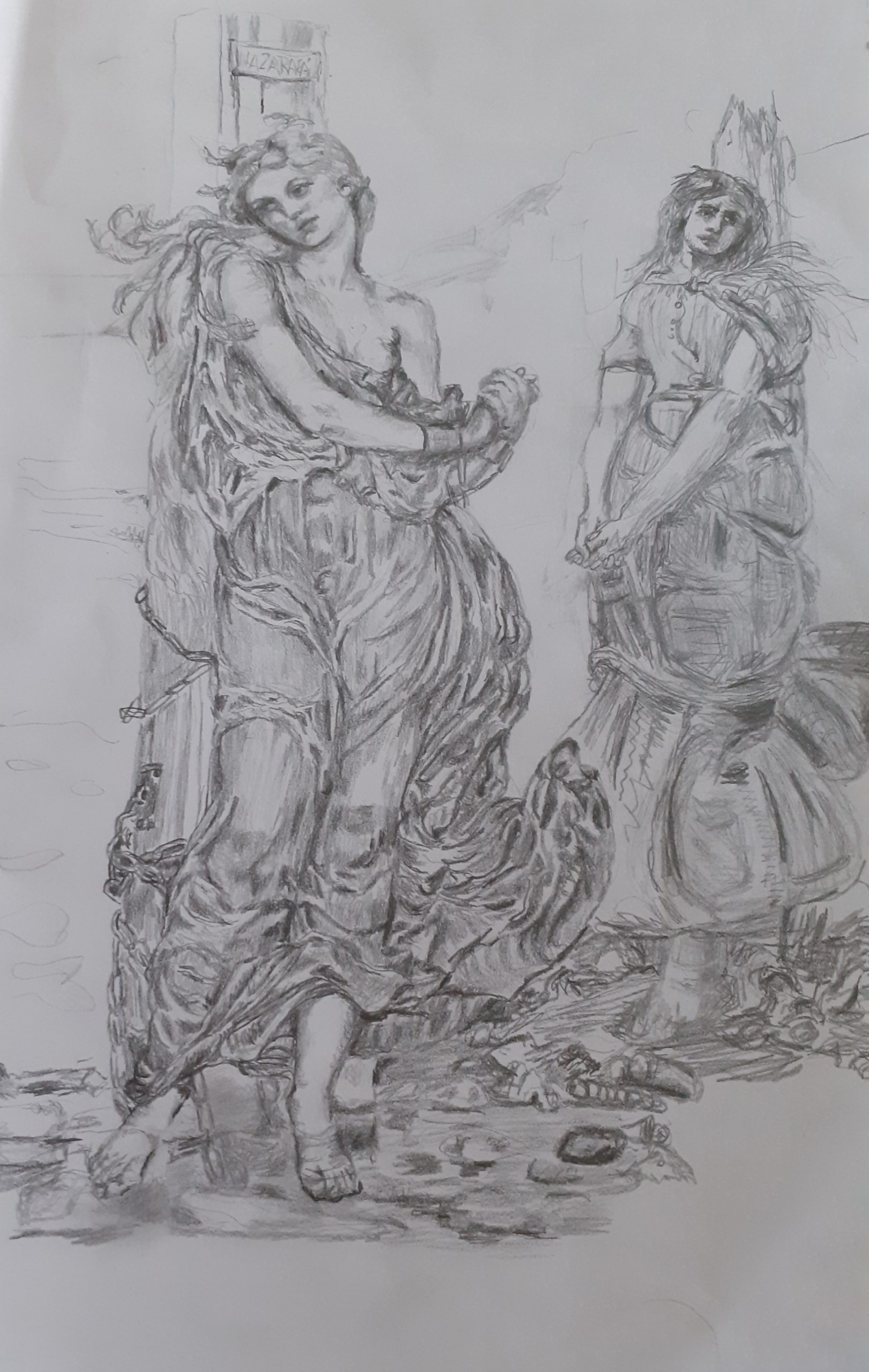

This week, I was asked if I would like to take a closer look at Evelyn De Morgan’s (1855-1919) The Christian Martyr (1880). I did not hesitate for a second, De Morgan was an extraordinary draughtswoman, portraying the human form with outstanding accuracy, and her portrayal of fabric is phenomenal. By drawing from her paintings, I hope to improve my own ability of depicting cloth. Each time I attempt to render her flowing fabric, I find the prospect very exciting, it stretches my resolve leaving me feeling satisfied when the cloth is completed not as an exact copy of Evelyn’s, but to a level of learning that I find satisfying.

I read an article by Yates (1996) in the De Morgan foundation catalogue, that Evelyn gleaned her inspiration from Sir John Everett Millais’ (1829-1896) sketch that was published in Once A Week in 1862. The London periodical was popular from 1859 to 1880 printed by Bradbury & Evans. Bradbury & Evans was originally a printing business that expanded into publishing, established by William Bradbury (1799-1869) and Frederick Mullett Evans (1804-1870). Charles Dickens fell out with Bradbury & Evans over his magazine Household Words, they responded by publishing Once A Week in direct competition to his new magazine All the Year Round. Fredrick Evans daughter, Bessie (Elisabeth Matilda Moule Evans 1839-1907), married Charles Dickens son, also named Charles (Charles Culliford Boz Dickens 1837-1896) in 1861, I will leave it to you to decide who got the last laugh.

Once A Week carried illustrations, from notable artists including Holman Hunt (1827-1910), John Tenniel (1920-1914), John Leech (1817-1864), poems from Lord Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (1828-1882) and others. The publication did not appear to have draconian views of other publications of that time as it published important work by female writers, Harriet Martineau (1802-1876), Isabella Blagden (1817-1873) and Mary Elizabeth Braddon (18835-1915). I found some issues of Once A Week online (link at the bottom of the page), including the 1862 issue with Millais’ drawing, adding it next to my sketch of De Morgan’s The Christian Martyr for comparison of style, design and composition.

Sketching De Morgan’s Christian Martyr, I discovered more movement than I had first anticipated. The upper torso appears to twist to the right, the knees are slightly bent and pointing to the left in a classical ‘Contrapposto’ creating a dynamic pose. There are similarities between compositions as both have flowing tresses and billowing swathes of cloth draped around the Martyr’s limbs and torso, give both an overall romantic feel. When I started sketching the face of Millais’ version, I thought the eyes looked dark, sunken, almost as though all the flesh and life was removed with just the skull remaining. I liked how this created a juxtaposition between Millais and Evelyn’s romantic renditions, creating a whole new composition.

Aware that De Morgan’s allegoric paintings usually contain a social or political meaning, I attempted to discover who the Christian martyr was.

Helpfully there was an inscription below Millais’ drawing in the Once A Week periodical which read:

“MARGARET WILSON.

See Lord Macaulay’s History of England vol 1 page 501. Margaret Wilson’s epitaph, from Wodrow, in the Churchyard of Wigton, is as follows:

Murdered for owning Christ supreme

Head of his Church, and no more crime

But her not owning Prelacy,

And not abjuring Presbytery;

Within the sea, tied to a stake,

She suffered for Christ Jesu’s sake.”

Millais (1872)

This led me to read both Lord Macaulay and Wodrow, and unearth the background to the story of Margaret Wilson, although for completeness I feel I need to start a little further back.

The Roman’s colonised England around the first century, bringing with them the Catholic faith. We know that Henry VIII fell out with the Catholic church in 1533, forming the church of England in 1534. In 1592 the church of Scotland adopted Presbyterianism. The Scottish Kings believed they had the divine right to rule both church and state, in 1638 the Covenanters as they become known because they signed the Presbyterian National Covenant. However, Charles II (1662) made it illegal to be a Presbyterian, his soldiers were sent to hunt down any person that did not attend Sunday prays. Things became worse under James II (James VII in Scotland), from 1680 to 1685 became known as the killing times. Many Scots were persecuted, when captured, they were found guilty and murdered within an hour.

Wodrow wrote about two specific to our enquiry in 1721 in his history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland using eyewitness accounts and court records. The story was of a widow, Margaret Lachlane aged 63, and Margaret Wilson 18 years old, and her sister Agnes who was only 13 at the time. The Wilson girls’ parents diligently attended Episcopal services, relinquishing their faith. Margaret and Agnes’ brothers remained devout Presbyterians, encouraging the girls to follow them, they were forced to live wild in the hills. The sisters visited Margaret Wilson, 30th April 1685, but were betrayed by a neighbour to the authorities. All three were captured, sent for trial, and found guilty, their sentence was for them all to be drowned. Their father went to Edinburgh to plead for all three to be pardoned. Why the warrant to pardon all three was not signed is lost in history, but we do know Agnes’ sentence was changed to £100 fine. Mr Wilson’s belongings were stolen bit by bit by the soldiers, eventually he went from well to do, to dying in poverty. On 11th May 1685, the two Margarets were taken to Wigtown Bay, tied to a post in the sands, with the younger tied furthest from the rising flood of the Solway, so that she would witness the elder drown. The hope was that to see the widow drown would terrify her into taking the oath and swear allegiance to the King, but she refused. As the water engulfed her, witnesses claim she prayed and read aloud Psalms 25 from verse 7:

Do not remember the sins of my youth

and my rebellious ways;

according to your love remember me,

for you, Lord, are good.

Psalms 25:7

When the flood water had covered her head, the soldiers lifted up her chin and asked her again to swear allegiance to the King, she again refused, according to eyewitness she remained resolute and fearless calling out:

“May God save him, if it be God’s will!” Her friends crowded round the presiding officer. “She has said it; indeed, sir, she has said it.” “Will she take the abjuration?” he demanded. “Never!” she exclaimed. “I am Christ’s: let me go!”

Wodrow R. (1721)

Having heard this the soldiers then pushed her head below the water until she was dead. Wodrow was deeply affected by the story of the two Margarets, condemning these and the other heinous acts of murder during the killing times. He stated that the soldiers had become used to acts of evil, that even the soldiers called each other ‘Beelzebub and Apollyon’. William of Orange took the throne in 1689, a year later Parliament passed an act which re-established Presbyterianism in Scotland.

Although not related to the Solway Martyrs as the two Margaret’s are also known, I feel it an opportune moment to mention that many of the Acts against witchcraft were not repealed until 1736. However, witch hunting continued, the last documented case was of an unknown woman, who was drowned by several of her neighbours in 1889. The last successful prosecution, resulting in imprisonment, of someone obtaining property by using witchcraft and sorcery recorded in the Old Bailey archives was of 32-year-old Susan Willis Fletcher in 1881.

The story of the two Margarets troubled Wodrow, I was certainly affected by such a heinous act, and am sure that Evelyn, as a humanist and feminist, was incensed, depicting how women have been persecuted throughout history, bringing this narrative to the attention of the public. Presbyterians, including Margaret, felt that no one had the right to rule the Church, except for Christ strongly disapproving of the pyramidical system of Bishops and Cardinals. Interestingly Cardinals still wear red, ready to shed blood for the church and Christ thus becoming a martyr.

Deveraux (2016) describes Evelyn’s Martyrs gaze as “serene indifference” going on to remark that Millais version is a sad sensual figure, although here he is discussing the oil painting rather than the sketch (The Martyr of the Solway by John Everett Millais (1871) Walker Art Gallery. 70-5cm X 56.5 cm oil on canvas).

He continues to exclaim that Millais version is fake, explaining that it looks like a Victorian model “dressed up” to play the part. I do not agree with that analogy, looking at the what I consider is a beautiful painting of a terrible event, has an air of composed indifference, the clothing is timeless and the hair colour is an intelligent assumption that Margaret Wilson being of Celtic blood would have log tresses of auburn hair. I feel De Morgan’s martyr dressed in red drapery has a classical feel, like so many of her narratives the female is placed centrally within the canvas implying that she is the master of her own destiny. Once you are aware of the story of Margaret Wilson, I think you would agree that she was in fact the master of her destiny. I do however like the statement by Devereux; “Evelyn effects (the) transformation, changing drapery to flesh in such a way as to sanctify the entire figure”, I had not thought of the way De Morgan handles drapery in this way before, but since reading that statement I feel that that is in fact a fitting analogy. De Morgan’s, social and political views are powerfully portrayed within this picture, donating this picture to the Southwark art centre for the people of Southwark for the ordinary person to have the benefit of this story perhaps to raise awareness to the plight of women and bring about change.

Another review that I do not agree with is the review that was printed in 1882 in The Spectator.

“………..artists whose work lacked meaning, because it lacked all touch of every- day nature and emotion……………..This young lady in her red drapery is less like a living, breathing being, than one of Cimabue’s virgins ;……………………..we cannot help feeling that her proper place would be in the stained-glass window …………….paint it with cheerful as well as sympathetic eyes, she might give us some very fine work.”

The Spectator Magazine 24th June 1882 p14

The editors of the Spectator were Meredith Townsend (1831-1911) and Richard Holt Hutton (1826-1897), it was a rule of the Spectator to have all articles written by anonymous journalists. It is known that Hutton did not have any formal art or art history training, his degree was in theology although he was never called upon by any church, turning to journalism as an outlet for his sermons, writing profusely about religion, art and literature. Whoever wrote for De Morgan to “go to Nature…. paint it with cheerful ….eyes” demonstrates the author of this review did not understand the tragic narrative. The only paintings within this exhibition that appears to have impressed this journalist were of, or by famous rich people. I do not feel this review would not have hurt De Morgaån personally or professionally, the following year she met William De Morgan, they married in 1887, her art was so successful she was able to support the couple and William’s ceramic business

Bibliography

Bradbury. W. and Evans. F. M. (1862) Once a Week An Illustrated Miscellany of Literature, Science & Popular Information Volume VII June to December 1862. London: Bradbury & Evans, London P42, University of Toronto. https://archive.org/details/onceweek07londuoft/page/42/mode/2up

Castelow. E. Witches in Britain https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Witches-in-Britain/

The Church of Scotland. Our Structure: History. https://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/about-us/our-structure/history

The Covenanters; The fifty Years Struggle 1638-1688 http://www.sorbie.net/covenanters.htm

Devereux. J. (2016) The Making of Women Artists in Victorian England: The Education and Carrers of Six Professionals. Mc Farland.

Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) De Morgan Collection. https://www.demorgan.org.uk/discover/the-de-morgans/evelyn-de-morgan/

Lord Macaulay T. B. (1848) 1800-1859The History of England from the Accession of James II. vol 1 (of 5). Philadelphia Porter & Coates. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/55901/55901-h/55901-h.htm

The National Archives. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/early-modern-witch-trials/

The Old Bailey Archives https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=def1-406-18810328&div=t18810328-406#highlight

Royal Academy. Bradbury and Evans (London) https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/organisation/bradbury-and-evans-london

The Martyr (Nazuraea). Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) Southwark Art Collection. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-martyr-nazuraea-193254

The Martyr of the Solway John Everett Millais (1871) Walker Art Gallery. 70-5cm X 56.5 cm oil on canvas. Liverpool Museums. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/martyr-of-solway

Wodrow R. (1721) The history of the sufferings of the Church of Scotland from Restauration to the Revolution. James Watson P246 – 250 https://ia802602.us.archive.org/26/items/histufferi01wodr/histufferi01wodr.pdf