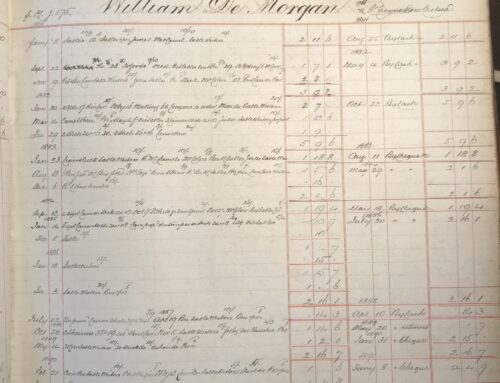

De Morgan Volunteer Sonja investigates the ideas behind Victorian interior design in this week’s blog. She allows us to put the De Morgans’ artworks into the context of the domestic settings there were intended to adorn.

In the Victorian era, middle class households placed great emphasis on the decoration and ornamentation of their public rooms, for example, the formal parlour. Much importance was placed on such decoration because it signified family economic success and social prestige. Moreover, the social philosophy of this age, was predominantly concerned with improving society and its people. Refined and beautiful decoration suggested a better human nature, and was a sign of respectability, sophistication, and morality. If your household lacked good taste, then morally there was something amiss. Formal parlours and drawing rooms would be crowded with furniture and display items. A bare table or mantle was regarded as being of poor taste, so every surface would be decorated with many items. It also resulted in extensive decoration, for example, with decorative plaster, elaborate mouldings and woodwork, as well as a widespread use of wallpaper.

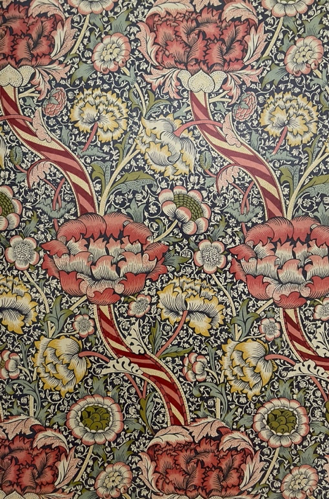

Wallpaper had become readily available due to mass production and the repeal of the Wallpaper Tax in 1836. Wallpaper consisted of elaborate floral and leaf patterns, sophisticated and finely detailed designs, such as those of William Morris (1834 – 96). Morris was a prolific wallpaper designer, and a proponent of the Arts and Crafts Movement, extolling the virtues of the craftman’s work as opposed to mass-produced items. Furthermore, Morris was critical of capitalism and industrialisation, the division it created in society, specifically between the rich and the poor and he believed it to be responsible for cultural decay. His predominantly plant-based designs, such as Wandle represented life, and challenged capitalism and industrialisation.

Wandle, printed fabric, manufactured by William Morris and Co. and Aymer Vallance, from Aymer Vallance, The Art of William Morris, Calmann and King, 1897. Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library.

Wandle, with its plant-based forms is suggestive of organic growth and social transformation as it entails ‘a healthy, pulsating and vibrant ecosystem in which plant and animal forms suggest natural harmony, development and social solidarity.’ (Edwards, 2012). Morris’s message of social criticism was echoed in paintings of interiors in this era too. During this period paintings were made predominantly for the domestic environment, as Britain at that time lacked state patronage, and artists relied on sales to the middle-classes. These paintings were predominantly genre or narrative paintings, depicting ‘bourgeois’ topics. They depicted pleasures and were moralising in nature, suggesting appropriate modes of bourgeois behaviour. One such example, is Robert Braithwaite Martineau’s The Last Day in the Old Home, 1862 with a very clear moral message, that gambling and drinking leads to debt and the loss of one’s possessions.

Robert Braithwaite Martineau, The Last Day in the Old Home, 1862, oil on canvas, 107 x 115 cm. TATE, London

It is evident that Robert Braithwaite Martineau (1826 – 1869) was a pupil of William Holman Hunt because this painting bares the same painstaking detail seen in the works of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and it addresses social themes. The dark interior is reflective of Victorian taste for heavy oak furniture and carved panelling. The room is wallpapered, has plush furnishings – the carpets and curtains, many artworks and the ornate fireplace is laden with most likely family armour. There are plenty of visual clues here depicting how the gentleman has gambled away the family fortune on alcohol and horses, represented by the father’s glass of champagne, and the sporting print in the foreground. On the left the solicitor is going over the deeds, while the distraught grandmother watches on. Lot numbers on various items shows that their possessions are to be sold. The father introduces his son to alcohol, suggesting the son will carry on with this hedonistic lifestyle, and his wife ‘is the moral hinge of the composition, bridging the two areas, beckons to the boy, calling him to follow the path of virtue and duty.’ (Edwards, 2012).

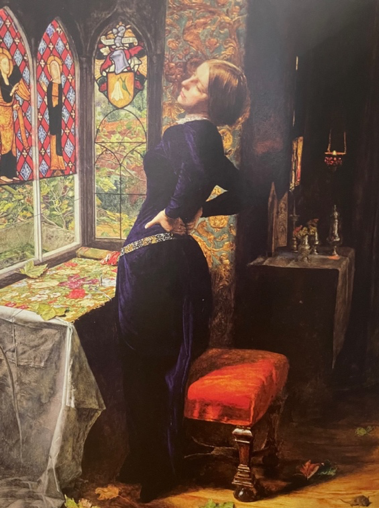

John Everett Millais (1829 – 1896) depicts an interior scene in his painting Mariana, 1851, which, while different from Braithwaite Martineau’s painting, contains moral messages too.

John Everett Millais, Mariana, 1851, oil on panel, 60 x 50 cm. TATE. London

Millais depicts an idealised version of female beauty. Here, the female itself acts ‘as antithesis to the world of commerce […] one that would be more beautiful and less constrained.’ This is emphasised by her surroundings, the decoration and her behaviour among these surroundings. On the table there is embroidery, which ‘was one of the standard accomplishments of femininity that encapsulated the home-bound values of decorum through patient, decorative work.’ (Edwards, 2012). Then, the religious elements – such as the annunciation of the Virgin on the stained-glass panels and the shrine in the corner, suggest Marian devotion, and the importance of religion towards leading a good and morally correct way of life. The fallen leaves indoors connect her to the outside world, while her life seems beautiful and less constrained by the trappings of modern life.

Sources

Edward s, S. (2012) ‘Victorian Britain: from images of modernity to the modernity of images’ in Edwards, S., Wood, P. (eds) A226 Book 3 Art and Visual Culture 1850-2010, Modernity to Globalisation, London and Milton Keynes, Tate Publishing in association with the Open University, pp.53-89. (Reprint 2013).

http://art-now-and-then.blogspot.com/2016/02/victorian-interiors.html

http://starcraftcustombuilders.com/Architectural.Styles.VictorianInteriors2.htm

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/martineau-the-last-day-in-the-old-home-n01500

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-mariana-t07553

https://victorianweb.org/art/design/conferences/interiors.html