A paper I gave at the Truth and Beauty Symposium at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Fransisco in October 2018.

Evelyn De Morgan was a truly radical artist whose work is a visual representation of her rebellion against the class and gender conventions of the middle class, patriarchal society she lived in. Her unique visual language combines her interest in Italian Renaissance painting, her revolutionary and progressive art training and her passionate beliefs in spiritualism, women’s suffrage and pacifism. Despite this, Evelyn is seldom recognised in Art History as the subversive and powerful artist that she was and her work is simply included in the literature about movements with which it was stylistically similar, in particular, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In this paper, I will introduce Evelyn De Morgan and give a brief overview of her art and life, before comparing two of her most arguably Pre-Raphaelite style paintings to two seminal Pre-Raphaelite paintings, to demonstrate that Evelyn De Morgan is not a Pre-Raphaelite artist.

Furthermore, I will present the idea that she went as far as to use a Pre-Raphaelite style to satire the movement, or to betray the Brotherhood’s beauty.

Evelyn was a fiercely independent young woman, determined to subvert the restrictions placed on her by society in order to become a professional artist. She was born to upper class parents in London in 1855, and christened Mary Evelyn Pickering. She elected to be called Evelyn, most likely because it is gender neutral and, as such, I refer to her as Evelyn throughout this talk. Her upbringing afforded her an education and an art tutor, however meant that her aspirations were rebuked by her parents who wished her to be a debutante, her mother once commenting ‘I want a daughter, not an artist’.

Evelyn rebelled against the ideals of femininity and the bounds of polite society to train as an artist, firstly at the National Art Training School in South Kensington before earning her place at the newly founded Slade School of Art. The Slade was established from the bequest of Felix Slade, a wealthy Victorian lawyer, philanthropist and art collector, which funded three professorships in Fine Art at University College London, Cambridge and Oxford. An additional endowment of six scholarships was left to UCL which led to the establishment of the Slade School of Fine Art in 1871.

As reported by Charlotte Weeks in Women at Work: The Slade Girls (October 1871) ‘here for the first time in England, indeed in Europe, a public Fine Art School was thrown open to male and female students on precisely the same terms, and giving to both sexes fair and equal opportunities.’ Evelyn was one of the first three female artists to be admitted and was therefore a trailblazer in quashing the myth that women were not physically able to become professional artists. She was able to take classes in life drawing, which would not have otherwise been available to her and proceeded to win a silver medal for her life drawing and a scholarship for studies, proving she was a perfectly able and credible artist despite being a woman.

Evelyn’s early work echoes the Neo-Classicism of Sir Edward Poynter, the first president at the Slade School of Art, under whom she studied. These paintings were fashionable and commercially successful. She was also clearly influenced by the Aesthetic Movement of the 1860s. However, whilst her male counterparts used female figures for decoration, Evelyn uses narrative to explore feminist themes. In Night and Sleep for example, the central female figure of Sleep spills opium poppies over a barren landscape, indicating the crisis of women becoming addicted to the opiate drug laudanum. Similarly, Ariadne in Naxos invites a feminist reading of the subject. Her abandonment by Theseus is usually represented by her in a mad rage, or as a symbol of lust when she is later discovered by Bacchus. Evelyn’s depiction of her as truly destitute reads more like a depiction of a fallen women, addressing the wider issue of women abandoned by society.

Despite being a young, single woman, who for her own safety should have been accompanied by a chaperone, Evelyn would often walk through London and indeed travel abroad alone. Her resistance to conforming to gendered behaviour allowed her the freedom to travel and she did so to Italy often, where she would stay with her uncle, the artist John Roddam Spencer Stanhope near Florence. Evelyn became well acquainted with Italian Renaissance painting and particularly admired the work of Botticelli for his draped figures and frieze-like interiors and landscapes, evidenced in The Garden of Opportunity (1892) and her masterpiece Flora (1894).

On her seventeenth birthday, August 30th 1872, Evelyn wrote in her diary: “At the beginning of each year I say ‘I will do something’ and at the end I have done nothing. Art is eternal, but life is short”. The frail nature of life referred to in this profound statement is a theme which haunts Evelyn’s artworks.

From about 1900, Evelyn began to more overtly depict themes of Spiritualism. Her marriage to William De Morgan in 1887 had introduced her to his mother, Sophia, a social reform campaigner, abolitionist, anti-vivisectionist and practising medium. Through her links with Sophia, Evelyn’s interest in the soul after death becomes more evident. In the Soul’s Prison House (1889) and The Prisoner (1907) we are presented with a young woman representing the soul, trapped in the prison of the body, with a hopeful sunrise, representing the dawn after death. These paintings hold dual meaning as of course they represent the entrapment of women in a patriarchal society. Many of Evelyn’s paintings celebrate both the rise of the soul through life towards freedom in death and the rise of women towards emancipation. Daughters of the Mist bonds solid female forms in prismatic clouds as they ascend to the point where the light shines from them. Evelyn paints a number of pictures in these bold pastels and they are her most Symbolist work.

Evelyn lived through the Crimean War, Boer Wars and WWI and the horrors of war troubled her deeply. Unable to convey her abhorrence of war with realistic, narrative imagery of the front line, Evelyn uses her own unique visual lexicon of symbols to present her pacifist ideals without resorting to violent imagery. In S.O.S (1914) the lone figure of hope cries out from the stormy, infested waters towards the end of conflict, whilst The Red Cross centres of the figure of Christ in blood red robes alongside the many dead in their unmarked graves, again offering hope of salvation. Both of these canvases were exhibited in the 1916 exhibition Evelyn held to raise funds for the British Red Cross and Italian Crocce Rose.

Around 30 years before Evelyn began her formal art training, The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848 by three young, professional, male artists. They sought to overthrow the art establishment and challenge social concerns by looking to the art of the past for their art of the future. They succeeded in doing so, with their provocative history and religious paintings, executed in minute, photorealist detail. What the Brotherhood also created however, was a male-centric visual landscape which appeased the Victorian patriarchal society they were created for. The title of their short-lived publication ‘The Germ’ demonstrates how they saw themselves as a force that would infect the establishment and how they, as a masculine brotherhood, consciously sought to aggressively penetrate all aspects of the art world.

The first painting which founder member John Everett Millais signed PRB was Isabella (1848) and it served as a manifesto for the Brotherhood. It’s allegiance to Old Master paintings and classical narrative, bright colours and microscopic detail set out the Brotherhood’s aesthetic aims. The subject of the painting is Isabella’s jealous brothers who seek to destroy their assistant Lorenzo and his love for their sister. The foreground of the painting is filled with male aggression in the brother’s leg which slices through the picture and the phallic shadow his arm casts on the table cloth. This painting also served as a manifesto for the avant-garde male painters’ radicalism.

As we have seen, from a selection of her paintings which explore the key themes of her artwork – of feminism, spiritualism and pacifism – Evelyn was an artist with a social consciousness who worked to fulfil her own agenda. It would seem peculiar then, that after experimenting with Neo-Classical, Symbolist and Renaissance styles in order to put forward her socio-political views and eventually reconciling these with her own style, Evelyn would – after forty years as a professional female artist – turn to the most aggressive, male dominated art movement in recent history for inspiration.

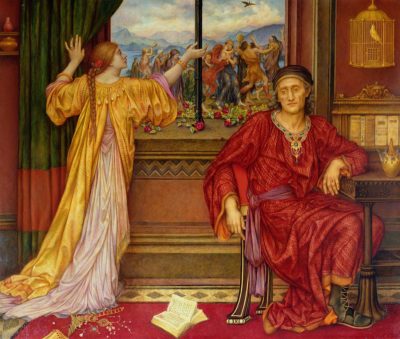

Evelyn’s The Gilded Cage (1900 – 1909) and The Hourglass (1909) out of the 100 or so known works by her are irrefutably painted in the Pre-Raphaelite style, but not because Evelyn was a Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood supporter.

William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience was painted between 1853 – 4, approximately 50 years before Evelyn De Morgan’s The Gilded Cage. Although The Awakening Conscience was a commission and remained in private collections until it was bequeathed to the Tate in 1976, it was exhibited widely in exhibitions which Evelyn would have been aware of, and it can be assumed that the painting would have been known to her.

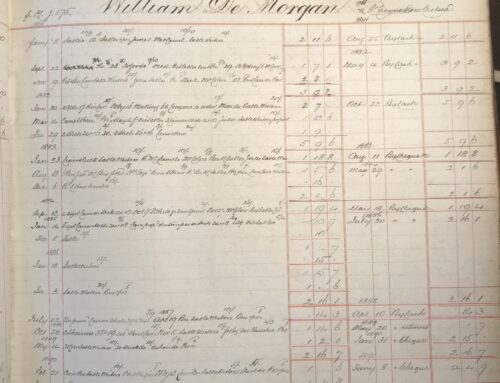

List of Exhibitions where the painting was exhibited in Evelyn’s lifetime

Pictures of Mr Holman Hunt, Fine Art Society 1886

Glasgow International Exhibition, 1901 (Fine Art Section, 391)

British Art Fifty years ago, Whitechapel Art Gallery 1905 (350)

The Collected Works of W. Holman Hunt, City Art Gallery Manchester 1906

Collected Exhibition of the Art of W. Holman Hunt, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1907

The paintings are incredibly similar, featuring interior scenes are rendered in minute detail with rich jewel-like colours creating an uncomfortable, gaudy interior with the main female character captivated by the world beyond the window setting her apart, in that moment, from her male companion.

Hunt’s scene depicts a ‘maison de convenance’ where a gentleman has installed his mistress. We see the moment that she has a moral awakening, realises the error of her ways and gazes into the light of redemption. She is defined as a mistress through her jewellery, only her wedding finger is bare and through her clothes as she wears loosely fitted smock which looks more like an undergarment. Ruskin wrote to The Times on 25 May 1854, ‘the very hem of the poor girl’s dress, at which the painter has laboured so closely, thread by thread, has story in it, if we think how soon its pure whiteness may be soiled with dust and rain, her outcast feet failing in the street’. It is as though she has not only acted in a morally wrong way towards the gent in this painting, but towards Hunt and his male audience for spoiling he well-painted dress she wears.

The blame and punishment in this painting – defined by male artist and affirmed by male critic – is entirely on the women. It is she who has done wrong, she who has awoken to this and she who is therefore in danger of being cast aside as easily as the gentleman’s glove. The male figure is without blame or need of moral awakening, with no consequences spelled out for him.

The Gilded Cage differs drastically from this painting in the artist’s placement of the blame and punishment. In direct contrast to Hunt’s painting, this is on the male figure, who represents patriarchal society. The jewelry worn by the female figure, again in direct contrast to Hunt’s picture, indicates her marriage – only the ring finger is adorned – and her imprisonment shown in the shackle-like bangles on her wrists. Rather than being the active, centre of the scene as in Hunt’s painting, Evelyn depicts the woman in the same plane as the husband’s possessions indicating a marriage of convenience which has entrapped her, much like the entrapment and objectification of women in wider society. The caged bird of course emphasizes this point. The window in Evelyn’s painting, like Hunt’s, provides a light to follow, however the raised level of the widow suggests something to aspire to, in this case freedom, as the window is closed and barred, not wide and welcoming as in Hunt’s painting. The emancipation she craves is not available to her. The moral awakening in Evelyn’s painting is embodied by the male character. Surrounded by his worldly wealth and learned material – his necklace is literally a weight on his shoulders and his bookshelf holds volumes on poetry, music and art – he realizes his wife’s unhappiness at being bound to him. It is as much a vanitas painting – a reminder that the inevitability of death renders material wealth useless – as it is a painting which calls into question the real value of woman as a possession in a marriage of convenience.

The inspiration for Evelyn’s painting, according to her sister and biographer, was the song The Yellow Bird from the 1903 musical The Cherry Girl, where a canary invites a sparrow to join her in her golden cage. When the sparrow refuses, choosing her freedom instead, the canary realizes she is trapped. The caged bird in Evelyn’s painting suggests a greater force or power that has taken the women’s freedom, clearly a critique of male-dominated society entrapping women. The bird in Hunt’s painting, it is worth noting, has been caught by a cat which suggests a provocation on the part of the bird, representing women being the natural prey for men.

Evelyn’s satire of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood is most stark in her 1904 – 5 painting The Hour Glass. This is another vanitas painting by Evelyn and clearly points to the passing of time and inevitability of death. The book lying open reads “Mors Janua Vitae” – death is the portal of life. Evelyn has clearly also used this canvas to convey her spiritualist beliefs.

By this point in her career, Evelyn’s spiritualist paintings had become less narrative and usually feature a female figure or groups of female figures together in swirls of rainbow mist, ascending skyward. Her use of the Pre-Raphaelite style in this canvas therefore, must also be read in order to fully comprehend this painting.

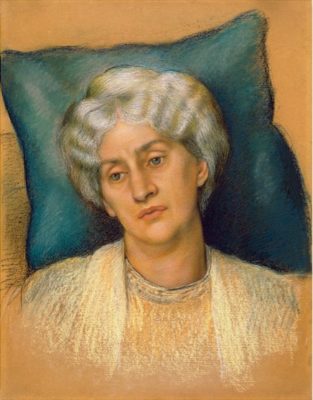

The model for this painting is the retired Pre-Raphaelite ‘stunner’ Jane Morris. She is pictured in in her old age, a wisp of grey hair can be seen just underneath the crown, and her hands have been painted with a gnarled, aged quality. She is depicted on a throne in richly detailed, sumptuous robes which almost overwhelm her. It is as though the Pre-Raphaelite style adornments are suffocating her.

Evelyn’s pencil sketch for this painting is a delicately studied, deeply accurate portrait of Jane Morris and is in stark contrast to her depiction by founder member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who of course was Jane Morris’ lover. Rossetti painted Jane many times and portrayed her as the Syrian goddess of love Astarte in his 1877 painting Astarte Syriaca. The contrast between this portrayal of Jane and Evelyn’s is stark. Here, Jane is objectified as sexual beauty. She stalks the viewer like a predator, stepping forward from the canvas, scooping her breasts and loose robe as though offering her body to us. Her enticing stare is direct and meaningful, her lips and eyes and hair are voluptuous and demand sexual attention. Rossetti chose to depict Astarte, the Syrian goddess of love, rather than Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Astarte is a more evil incarnation of love, a temptress hence the deadly nightshade on the torches in Rossetti’s painting. It is a painting of lust and sexual desire, not of love.

The Hourglass literally takes Rossetti’s queen of lust and transforms her into a sliver of her former glory, morbidly willing away the time until her impending death, shrinking away from decadent costume. She uses the Pre-Raphaelite’s model and style to show that their ideals of beauty have been destroyed by time.

Evelyn signed the declaration in favour of women’s suffrage in 1889 and lent her support again to the cause in 1897, signing a similar petition. In 1913, her husband, William, became the vice president of the men’s league for women’s suffrage.

Society was changing when Evelyn executed her most Pre-Raphaelite style paintings and the ideas of brotherhood, objectification of women and patriarchy were on the brink of being overthrown by some women getting the vote in 1919. Evelyn was not a Pre-Raphaelite follower, a second-generation Pre-Raphaelite artist and certainly not a supporter of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and its values, but was instead inspired by her desire for social change, to ridicule their artwork and the misogynistic values it had upheld some 50 years earlier. Thus, she betrayed the Brotherhood’s beauty for the advancement of her own, feminist ideals.