Painting the Female Nude

In the twenty-first century we can take pride in a history of female artists’ representations of the female nude. De Morgan often painted her model, Jane Hales, nude and this enduring celebration of the naked female form by a female artist, allows academics and contemporary audiences alike to interpret this art through the lens of queer art history. By assessing the fundamental differences between male and female artists painting the female form, we can improve our understanding of the circumstances in which De Morgan made her pictures, why she favoured the female form, and how her art fits into the art history canon.

Jane Hales aged about 17. Photographer unknown

Representations of naked female forms, mostly white, in European culture have existed throughout art history. For centuries these female figures defined ‘High Art’, the sexuality of these figures was permitted under the guise of mythological figures, nude female figures were represented as idealised gods not earthly women. From Titian’s sixteenth century representation of Venus of Urbino (1538) to Rembrandt’s Danaë of 1636. Later in the eighteenth century in Jean-Honoré Fragonard The Raised Chemise, 1770, this mythological context is only vaguely alluded and the sensuality of this canvas can be compared to Manet’s 1863, Luncheon, a modern woman has discarded all her clothes confidently and sits with fully clothed men. More recently Lucien Freud’s celebration of the fleshiness of the female form envelops the canvas.

The art historical canon has focused on these and other artworks created by male artists and stresses that they were made for male patrons, to be viewed mainly by men in private settings. Kenneth Clark’s seminal 1956 text ‘The Nude’, explored the manifestation of this binary, heterosexual desire- women were objects to be viewed by the male gaze. He discussed what the nude, and in particular the female nude painted by men signified. It is no surprise then that Suffragette Mary Richardson famously attacked Velázquez’s, The Rokeby Venus, in 1914 creating incisions in the canvas, later saying she disliked how ‘men visitors gaped at it all day long’, and the Guerrilla Girls artist and activist collective produced the iconic 1980’s protest poster- Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum? (1989).

Rokeby Venus, by Diego Velazquez. National Gallery, London.

Bacchante (1785) Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. The Met, New York

However where does that leave the representation by female artists of the female nude? Female artists have also, throughout history, represented the female form, nude within their art, and often sensuously. The erotic representation of Danae by Artemisia Gentileschi in 1612, can be compared to the classical mid-17th century, Venus Attired by the Three Graces created by Anne Killigrew, which also offers similar stimulation to Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s Bacchante, exhibited at the French Salon in 1785. Later, Laura Knight’s self-portrait- Laura Knight with model, Ella Louise Naper of 1913 and her contemporary, Susanna Valadon’s Reclining Nude of 1928 can be compared to Bianca Nemelc, recent work from 2019, Floating, which also depicts the curves and sensuality of a female figure, but in this art work a black female body is depicted. A contemporary female artist Jenny Saville argued that despite the descriptions of her nude female figures as lacking sensual beauty- ‘What is beauty? Beauty is usually the male image of the female body. My women are beautiful in their individuality.’

Women artist’s by their very presence, constructing the gaze, challenged this binary view of who was the object and who held the gaze. Lynda Nead’s seminal feminist text published in 1992, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality, critiqued Clark’s earlier study and discussed both male and female artists representation of the female nude, to unlock ‘a range of issues concerning the female body and cultural value.’ She examined the sexuality and sensuality of the nude; however, her focus was on the heterosexual gaze- ‘The female nude is also a sign of those other, more hidden properties or patriarchal culture, that is, possession, power, and subordination.’

Also, while we can’t negate the fact that for women artists and in particular Evelyn De Morgan, representations of nude figures in her finished paintings was an assertion of her talent and professional status as an artist – De Morgan was able to study the nude at the Slade School of Art, although women had historically lacked access to life drawing classes and therefore the nude. That doesn’t explain what I would argue is the sensuality inherent in these art works.

Creating nude studies as preliminary sketches for paintings was common practise for artists. The De Morgan Foundation collection has some incredibly skilled examples of Evelyn’s process- she draws the figure’s naked form first and then creates sketches of the figure draped/clothed. However, that Evelyn, chose to create a number of paintings featuring nude or semi-clad female forms is a bold statement for a Victorian female artist.

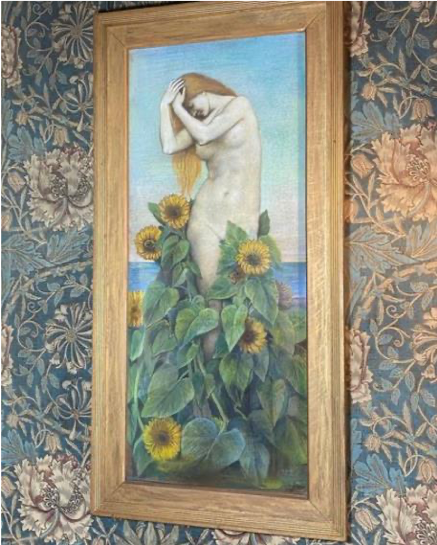

Evelyn De Morgan’s pastel sketch of Clytie of 1885, and the oil painting created from it, (both considered by Evelyn as artworks in their own right) are celebrations of the female form wrapped in the mythology of the goddess. The sensuality of the female come from the entwining, the touch of the sunflowers wrapping around her naked legs, as well as her arms that don’t quite cover her breasts. Strikingly in Frederic Lord Leighton’s representation of Clytie by comparison, a contemporary of Evelyn’s, the female figure is fully clothed with her back turned to the viewer with her focus on worshipping the sun. This comparison only heightens the sexuality inherent in Evelyn’s work. In her representation Clytie’s nude figure is foregrounded, the sunflowers caress doesn’t reach beyond her hipbone, and her body is tantalisingly exposed to the viewer. Her face however is shielded from us, her thoughts are her own.

Clytie with Sunflowers, Evelyn De Morgan, Pastel on paper,1885, Wightwick Manor, National Trust Collection, on display in the Honeysuckle bedroom.

The Sea Maidens, Evelyn De Morgan, Oil on canvas, 1885 – 1886, De Morgan Foundation Collection, currently on show at the Queen’s House’s gallery, Greenwich.

In both Evelyn’s representations of Clytie and The Sea Maidens, the femininity, strength and allegorical and literary significance of these figures is often discussed but when their nakedness is alluded to it is often distanced from any mention of sensuality or sexuality.

In The Sea Maidens this caress of the female body is again foregrounded but is here enacted by other women. Touch is the sensory experience highlighted in the painting. Each of the women are connected by the touch of each other’s hands. Some of these touches occur on or very near the breasts, while another’s is on the pelvic bone, drawing the viewers eyes to the sites of sexuality and sensualising the touch. The scaly tails of the mermaids also appear to be touching each other under the water. The queer sensuality of these figures is striking for a contemporary viewer. As with Clytie another disembodied caress is also represented. The lapping of the sea doesn’t quite reach the hipbone, foregrounding the pubic region.

In the three nude figures of Moonbeams Dipping Into Water the nude women are also shown to be connected through touch, through their hands and legs. The figure at the top of the canvas seems to be having her arm lightly stroked by the woman beneath her. The sensuality of the draping also, like the sunflowers leaves and waves, adds another erotic touch to the representations. As well as the hands and legs of the figures joining, the drapery connects the three figures. The drapery just covers the women’s genitalia, but isn’t stationery, like the waves it appears to be moving over these areas. The drapery is sensuously flowing over and caressing the figures genitalia, charging the erotica of the painting.

As an independent feminist painter, it seems that Evelyn De Morgan was keen to disrupt the patriarchal art world she inhabited. Whether intentionally or through contemporary reinterpretation, we can see that she did so subversively by taking ownership of the tradition of the heterosexual white male glaze in painting and using it to imbue her paintings with a powerful, revolutionary energy.

This story is the beginning of a research idea, there are so many more questions these ideas suggest.

How would we define Evelyn De Morgan’s nudes in the history of art?

How would we define it in relation to male artists work who directly inspired her and feature the female nude,

such as Botticelli? And how would we compare it to other female artists depictions of naked female figures?

Is it sensuality the focus of her representation of the naked female figure, or is it vulnerability or truth or another

quality?

Is Evelyn instead creating this art with an awareness of the historical and contemporary heterosexual male

patron driven art market and their tastes and desires?

Would queer viewers looking at these artworks when they were first created have seen this connotation despite

the lack of public censorship of her work- which would connote something obscene to Victorians?Or during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was the female sensuality, and the queer sensuality (often unheard of / unthought of, due to femininity and chasteness being synonymous) ignored in these art work, were they viewed as only classical inspired artworks, lacking the sensuality of male artists work?

Because it’s a female artist representing and celebrating the sexuality of the female nude do modern viewers

find a queerness in these representations?

Is queer desire implicit in the female artist and female nude model relationship in the viewer’s mind?

By Hannah Squire, independent art historian and curator

Moonbeams Dipping Into the Sea, Oil on canvas, 1900-1919, De Morgan Foundation Collection, (not currently on display).

Donate

We rely on your generous support to care for and display this wonderful collection